›Order and the disruption of order‹—this is how Achim Freyer describes the basic subject of his artistic work between 1965 and 1971. Mass societies, according to Freyer, strive towards serial production at the cost of individuality. The individual can only achieve acceptance as part of the community through uniformity, he is marked by the mechanisms of production. Freyer applies the critique not only to the cultural policies of the Eastern Bloc countries, he conceives of it as a fundamental critique of modernity. All the same, the artist becomes an individual disruptor. The series of pictures from the underground, in which anonymous faces appear as silhouettes or outlines, was the first expression of his engagement with mass society and the individual. One example of this is ›U-Bahnbild mit Individuum‹ (Underground Painting with Individual), in which the human faces have been robbed of all their individual characteristics.

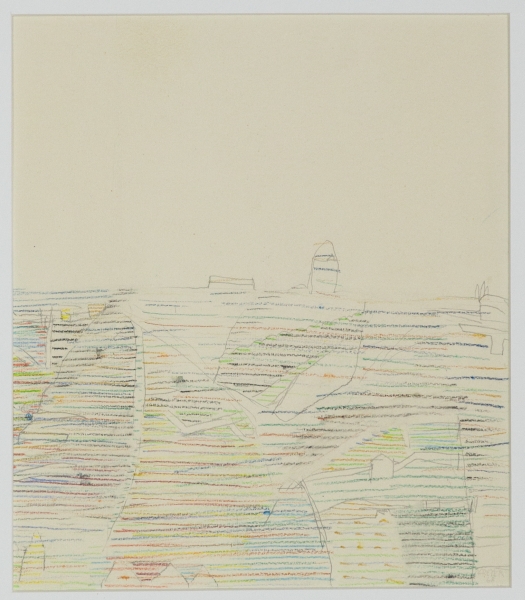

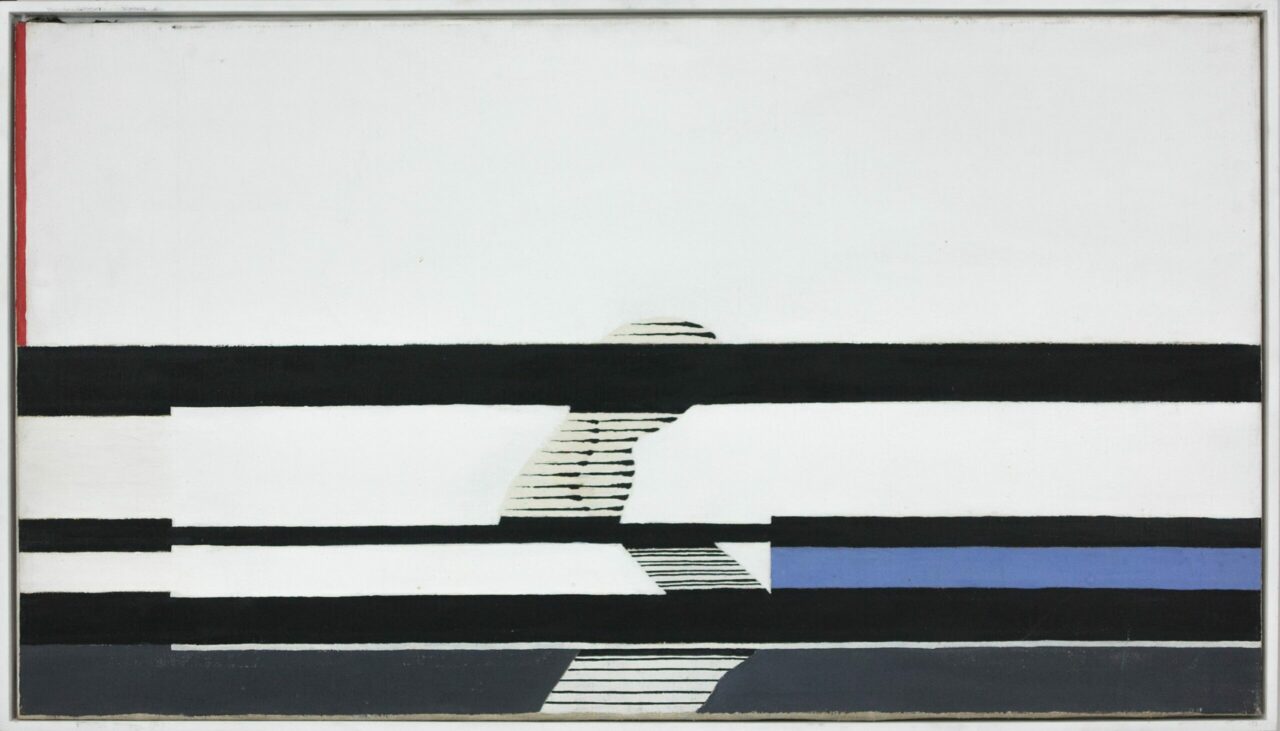

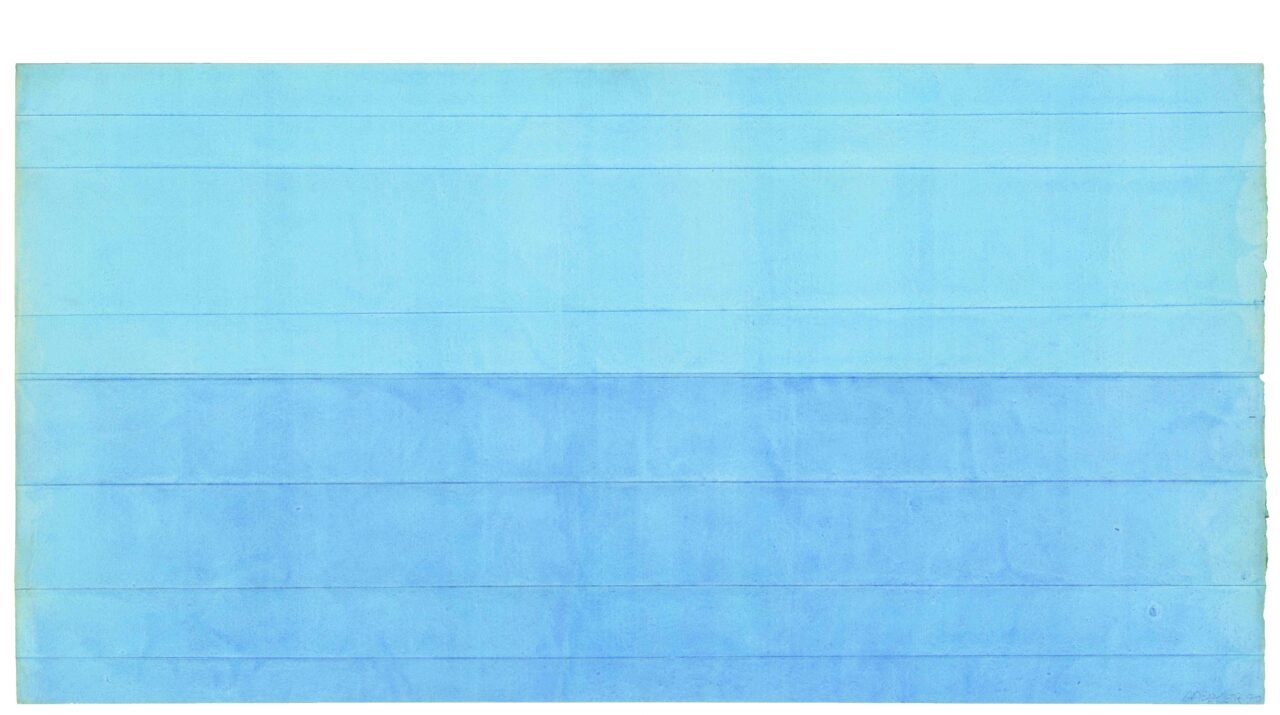

The small drawing in coloured pencil ›Weinberge aus bewegter Position‹ (Vineyards from a Moving Standpoint) from 1968 captures the painter’s experience on a train trip, where the rows of vines in the moving train become horizontal lines. This experience of his own time and perception became the initial inspiration for an entire complex of abstract works and an aesthetic recalibration. Horizontal lines became the definitive visual concept in his work. The more abstraction tends toward the horizontal in the image, the less individualities can come through. ›Vorübergehender‹ und ›Vorübergehende‹, two paintings from 1968, show the human silhouette in temporal extension, only partially breaking through the horizontal. The result is the formal transformation of figures to schemata and ultimately to radical abstraction. ›Seestück‹ (Marine Painting) from 1970 consists exclusively of horizontal lines that result from folding the image surface. This is a highly productive visual process that he then transferred to the stage. The horizontal stripes served as the design principle for the steps on the stage set used for Benno Besson’s ›The Good Person of Szechuan‹ at Berlin’s Volksbühne in 1970. The stripes describe the hierarchy, from the gods to the landlord to the slums. Achim Freyer realised the horizontal in its most radical form with the three pipes covered with vivid shades of paint and silver paper in stripes, refusing all strictures of GDR art policy.

On 25 June 1971, Achim Freyer’s first solo exhibition opened at Zentralinstitut für Kernforschung in Rossendorf, a town near Dresden. The institute was the largest scientific institute in the GDR, with around 1500 employees. The patron of the project was the cultural commission at the institute run by the Freier Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund, the GDR’s association of unions. Radiochemist Eberhard Gäbler, the initiator of the exhibition and patron of Achim Freyer, describes the work of the commission as follows: »There was some leeway because the exhibitions were not public, but only accessible to employees of the institute.« The approximately thirty paintings and objects that were exhibited from 25 June to 1 July 1971 mostly belonged to the series ›Streifen, Ordnung und Störung von Ordnung‹ (Stripes, Order and the Disruption of Order, 1967—1971). Until then, abstraction had not been shown in the GDR, with the exception of a Hermann Glöckner exhibition at the Kupferstichkabinett in Dresden in 1969.

In 1971, Adolf Dresen staged ›Clavigo‹ at Berlin’s Deutsches Theater, and Achim Freyer was responsible for set design and costumes. After the premiere on 7 December 1971, the production was cancelled because it used a visual language that was considered too Western. Freyer was banned from entering the premises. With his liberties constricted both in the fine arts and in the theatre, Freyer saw no alternative but to flee the country. During a tour of ›The Good Person of Szechuan‹ in northern Italy in 1972 with stops in Milan, Florence, Genoa, Turin and an exhibition in Florence, he was able to escape.

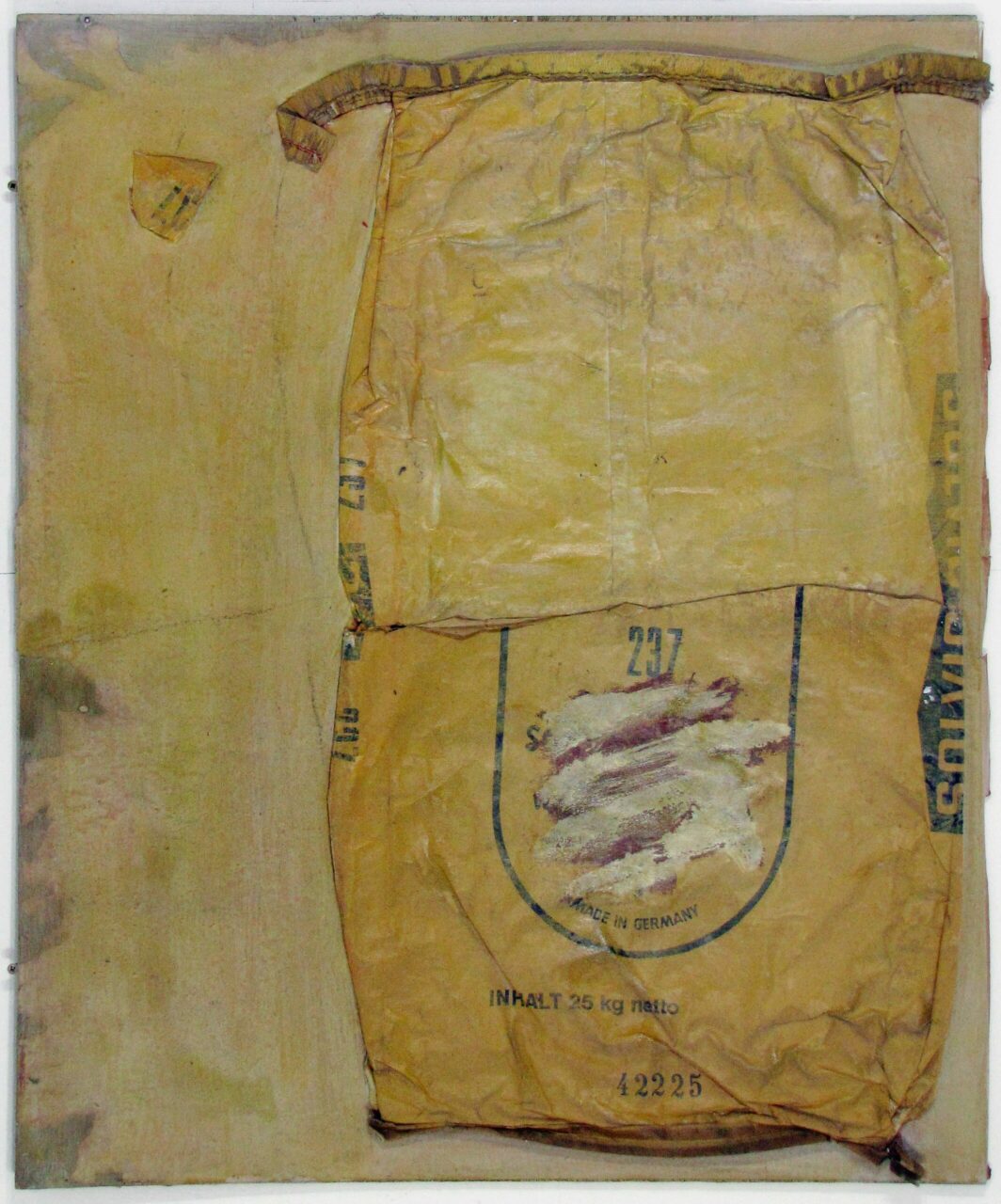

Changing sides became an artistic challenge for Achim Freyer. ›Shackled in freedom‹ is how he describes his own point of departure in the West. In contrast to the total abstraction of the horizontal from the period around 1970, he now relied on the sensuality of the used, the traces of decay, the vital. In his paintings and objects after 1972, Freyer was reacting directly to the new reality he experienced in the West »[I] was smothered by the cleanliness of the world in the West. The buildings were all painted snow white, so I had the sense I had to sink my hands into the dirt right away.«

For Freyer, the serial, abstract experiments in colour from the period before his escape now just seemed like imitations of American modernism. His installations using vivid colours, a provocation in the GDR, he now encountered at every petrol station in the West. Achim Freyer was confronted with the laws of the art market and art history, which did not allow for a parallel modernism in East Germany and Eastern Europe. Exemplary here was an experience he had with gallerist Alfred Schmela, who volunteered to purchase to all the works he had with him, offering 100 DM for each work. Freyer rejected the offer. Freyer reacted to the new situation with a series of human silhouettes that were painted with tempera, chalk, or coloured pencil on packing paper. The outlines that resulted, reminiscent of Oskar Schlemmer, are related to the figures of the underground paintings from the 1960s, seem to return in a new form, the legs bound together. The human being is shackled, shackled in and by freedom.

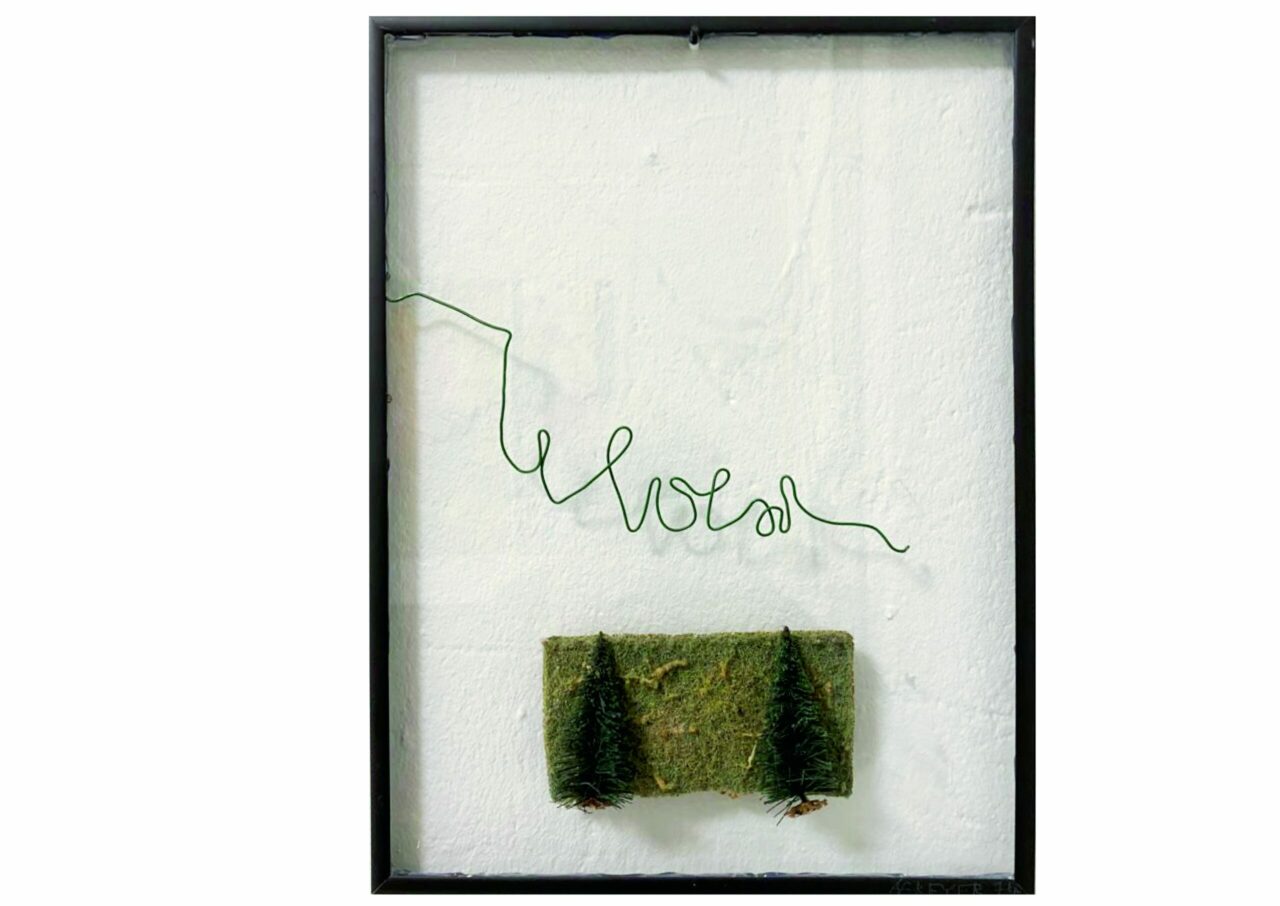

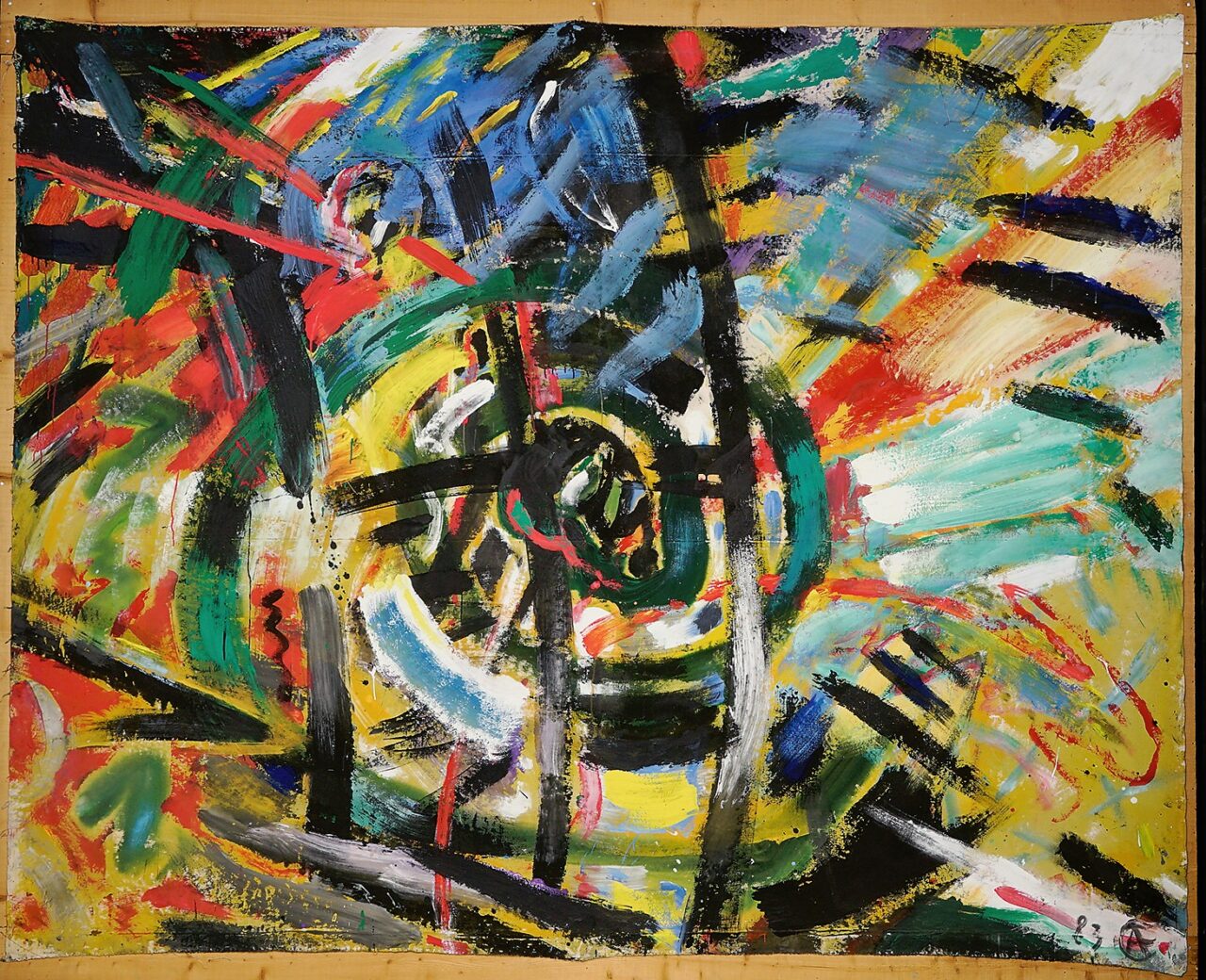

His assemblages and environments used found boxes and crates, collages with everyday objects, rubbish or small drawings and overpainting as their point of departure. They are not just a reaction to the polished surface of West German society, they are also descriptions of the state of inner injuries and wounds, which press outward and demand transformation. Towards the end of the 1970s, signs of a longing for home, a pine tree, forest, hare, or cross, surface near in his paintings, leading towards a phase of the ›Großen Gesänge‹ (Great Songs), as Freyer himself calls them, an extensive series of large-scale colour paintings created in the years up the 1984, a veritable cascade of paintings that culminated in the exhibition ›Achim Freyer: Malerei‹ (Achim Freyer: Painting) held at the Große Orangerie at Schloss Charlottenburg in West Berlin in October 1983.

Freyer dedicated himself increasingly to issues of expanded painting, not by way of the use of found objects, but especially by expanding visual ideas in spatial constellations. He took another step with a series of environments. This artistic extension towards installations and temporary monuments, such as ›Monument des Heinrich von Kleist‹ in Stuttgart in 1975, culminated in 1977 with the artist’s participation at documenta 6 with the environment ›Deutschland, ein Lebensraum‹ (Germany, A Habitat).

documenta 6 made clear the extent to which Achim Freyer was implicated in the cultural politics of the East/West divide. And how much he was concerned with his own position as a person without a homeland in divided Germany. The fact that this led to a unique, productive dynamic, is fortuitous for us all, for fine art, for the theatre, and for Achim Freyer himself.

Achim Freyer is accompanied by a life-long stream of painting through which he communicates and connects with the world. In the sense of ›One Thousand and One Nights‹, Freyer means a narration that saves our lives. It is only by continuing the narration that Scheherazade can survive. Only through such an existential perception can we understand how Freyer continues to paint uninterruptedly. And just as the stage provides him with the room to reorder all linguistic elements, a language that we dream, that allows us to rise up when we experience silence, the painting surface is used to communicate an inner path of suffering, becomes a motor of a lifelong narration, driven by the yearning to overcome loneliness and silence. It is a fragile path and at the same time a powerful force responding to inner and outer abysses, to death and war. »Making destruction impossible through sensitization, through tenderness and power. If that succeeds! I have to paint, I cannot do otherwise. This unconditional drive. No critical mimesis of war and destruction can help here. It must be a counter-image.«

Like his teacher Bertolt Brecht, Freyer relies on a critical attitude with a simultaneous struggle to achieve lightness, the beat of a butterfly wing: »I suspect a great liberty and lightness that is expressed in painting, but that has to agree with the reality of life. The freedom I am referring to is a motif for the direction I take, but no a chance at being. The body is a shackle just like the environment. But in this way, the longing for the beat of a butterfly wing is so great because we cannot exist without this dimension of the moment.«

Biography Achim Freyer

The painter, dramatist, collector, and professor Achim Freyer was born in Berlin in 1934. After completing his studies at the Fachschule für angewandte Kunst in Berlin-Schöneweide in 1955, he became an apprentice to Bertolt Brecht: due to the restraints placed on artistic creativity, he fled to the West in 1972. He became one of the key artists of post-war modernism and famous worldwide as a director, set designer, and costume designer. As an artist, he participated in documenta twice, in 1977 and 1987. The constantly growing body of work by Achim Freyer has been exhibited in numerous exhibitions in Germany and around the world, in Los Angeles, Venice, Vienna, Tel Aviv, Berlin, Moscow, and Seoul.

The retrospective ›Achim Freyer: Bilder‹ at Schloss Biesdorf is the first exhibition to present Achim Freyer’s artistic oeuvre spanning over seventy years in a larger context.