This article was first published in the Museumsjournal.

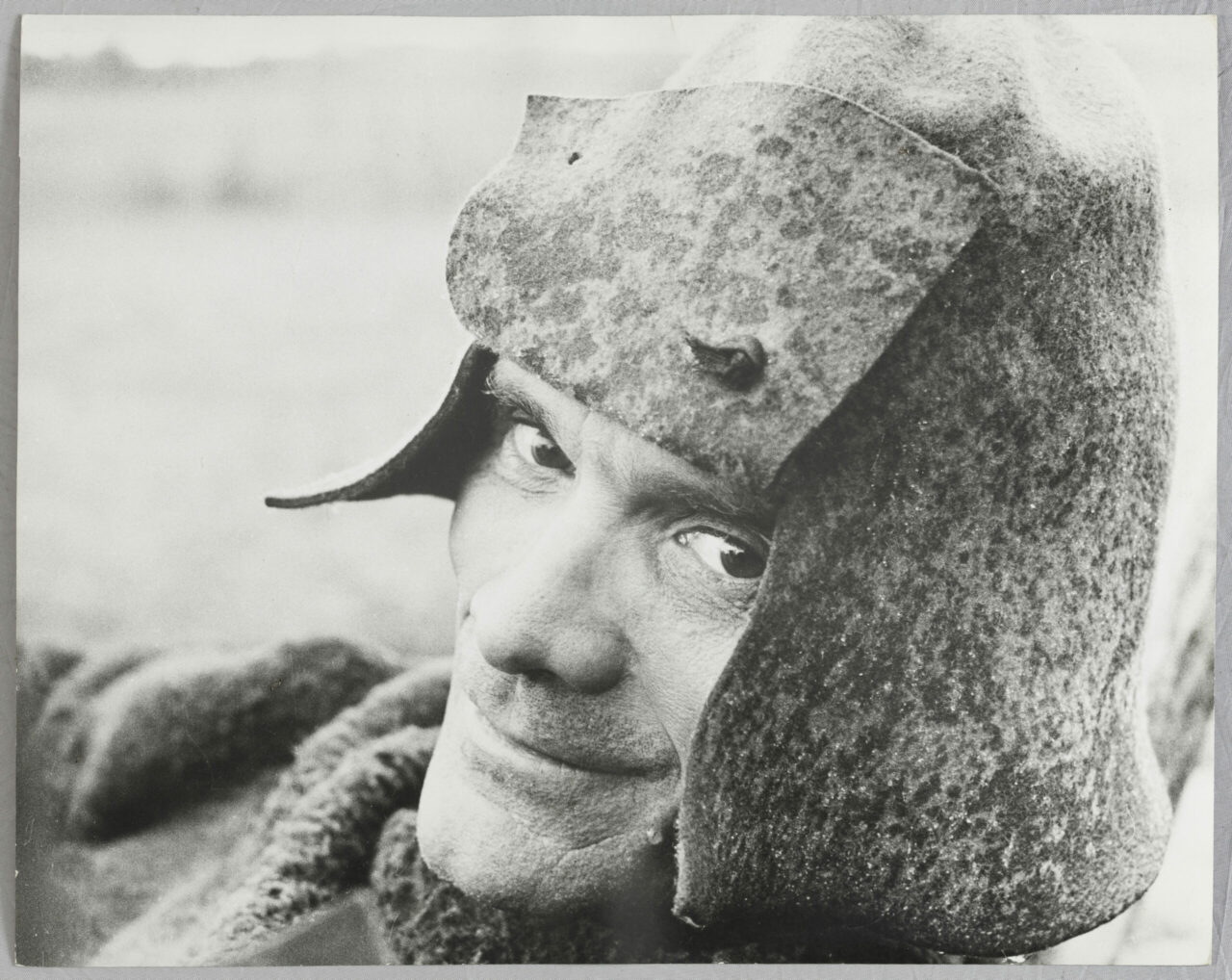

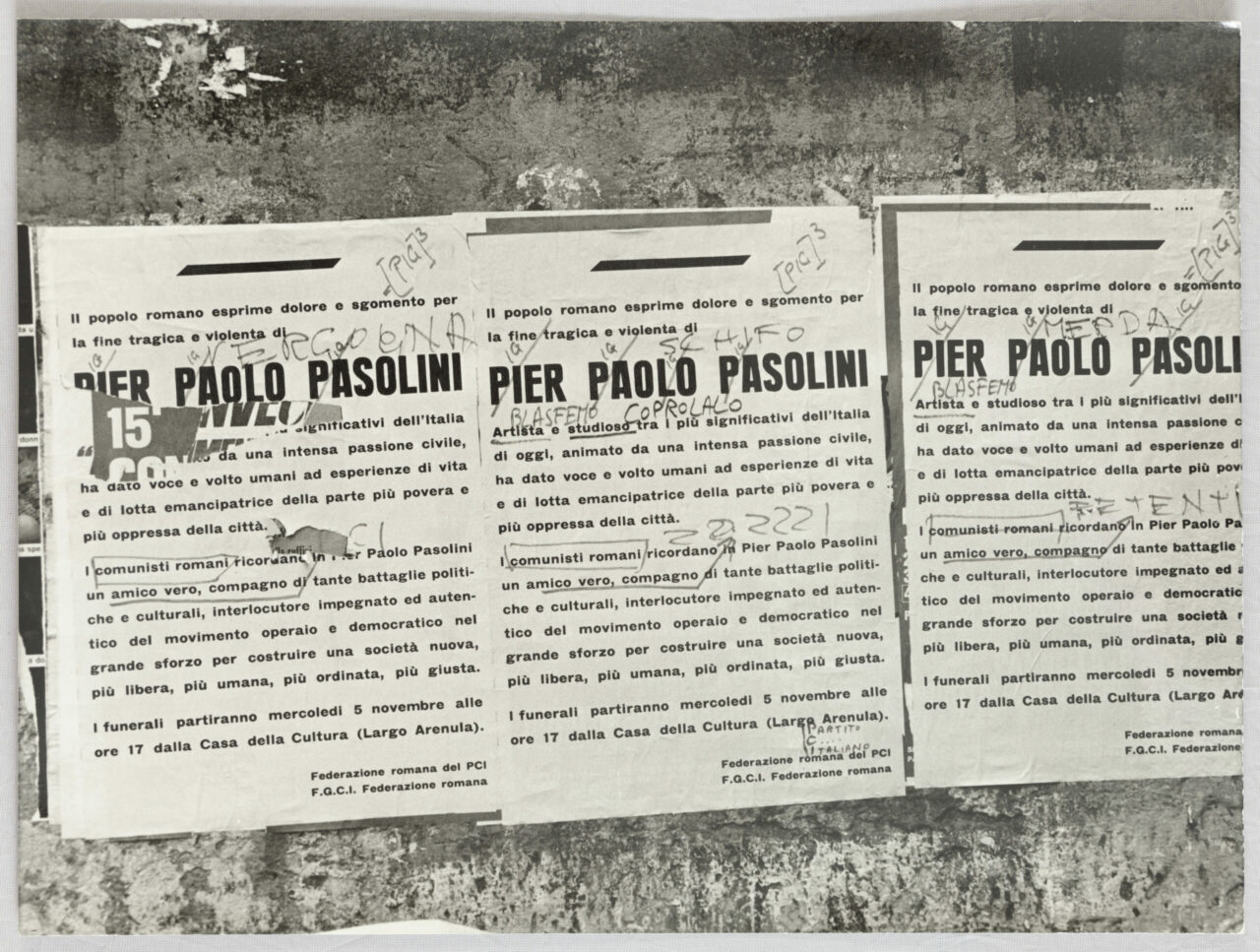

Pasolini’s life and his position within the Italian cultural landscape and politics from the 1950s to the 1970s met with rejection and disgust, primarily due to his membership in the Communist Party and his open homosexuality. His books, newspaper articles, and films and especially his sheer physical presence were the cause of numerous scandals and provoked reactions ranging from public ridicule to legal persecution. In 1975, he was murdered under unclear circumstances; his body was found on the beach near Ostia. The exhibition at n.b.k. chronicles these events. The hundreds of documents presented are the result of meticulous research, but avoid all mystification, revision, or hagiography of Pasolini as a figure. They present the brutality of his persecution and the relentlessness of the media reporting that consisted in reporting rumours, accusations, insinuations, threats and targeted insults.

The exhibition begins with a ›wall of trials‹: at the entrance of the exhibition, visitors encounter a long wall that documents the numerous trials that were carried out against Pasolini. He was charged with pornography, obscenity, defamation of religion and lese-majesty. Although numerous accusations ultimately proved to be unfounded, all legal means were exhausted in prosecuting these purported crimes, even the most unplausible among them, such as the accusation that Pasolini committed armed robbery at a petrol station using a pistol loaded with golden bullets. As legal expert Stefano Rodotà established two years after Pasolini’s murder, the artist was almost constantly involved in legal battles from 1960 until his death in 1975. The trials were intended primarily to cast doubt about the legitimacy of the social and cultural existence of a figure like Pasolini. No aspect of his public work, no corner of his private life was protected from defamation and denunciation. Neofascist groups saw physical attacks against Pasolini as a kind of moral duty and proudly displayed them. At the same time, Pasolini was subject to repression from the state and all its institutions.

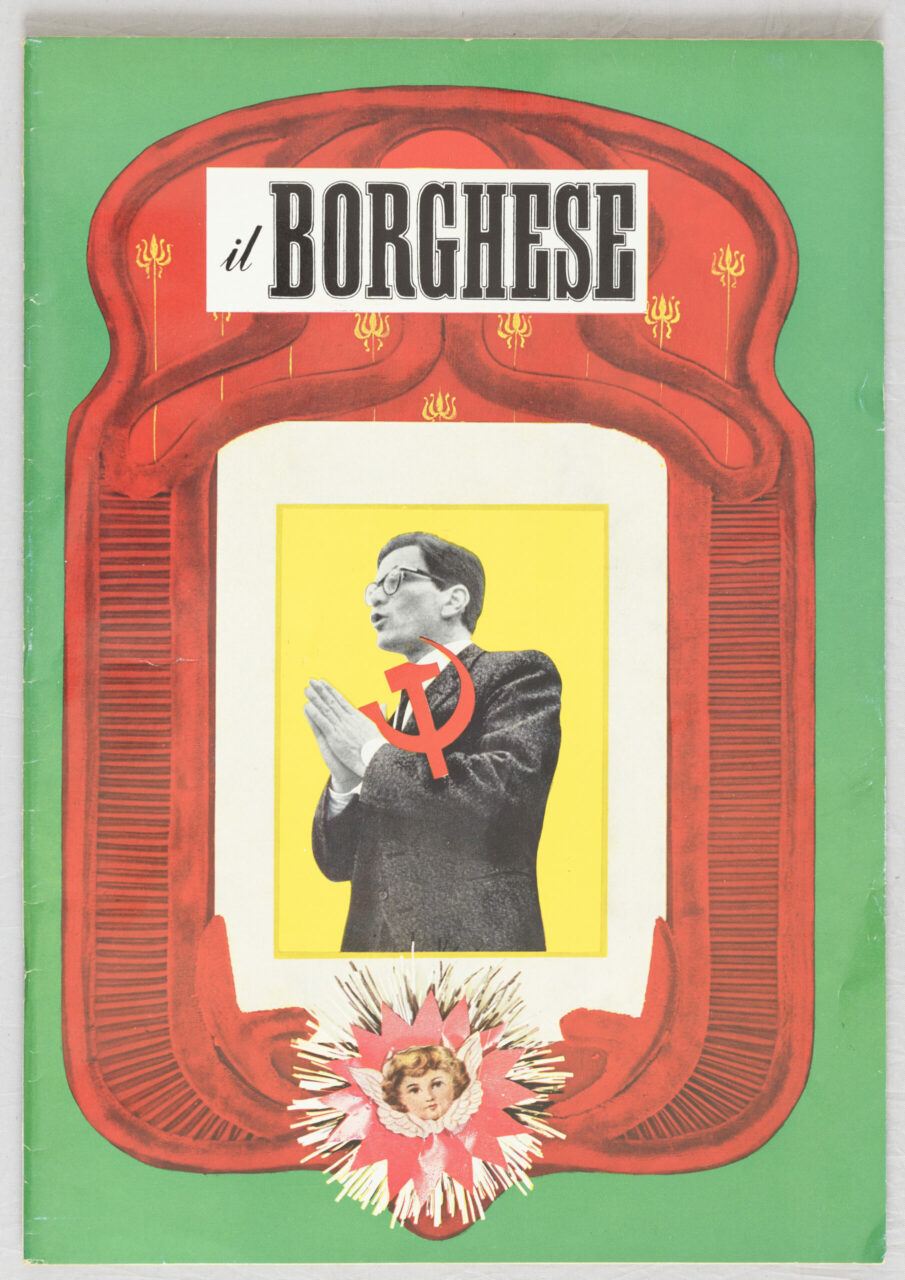

At the n.b.k. exhibition, numerous caricatures, jokes, and photomontages from newspapers, magazines, and weeklies are on view that mock Pasolini as a writer of the subproletariat and ›poet of scum‹, continuously referring to his sexual ›deviance‹. The bourgeois and patriarchal world of Italy felt threatened in its masculinity by the openly gay Pasolini.

An additional section of the exhibition is dedicated to the scandal around the film ›La ricotta‹ (1963), for which Pasolini was convicted of religious defamation. The prosecution demanded that a Moviola be set up in the court room to analyse the film scenes in question meticulously in order to show blasphemous intent. In particular, the scene in which Christ falls down during the descent from the cross and then bursts into prolonged laughter with Mary Magdalene, John and the angels was dissected and discussed in detail.

In additional sections of the exhibition, Pasolini’s artistic interests in even more provocative subjects are explored. In the film ›Porcile‹ (›Pigsty‹, 1969) cannibalism and erotic zoophilia are represented emblematically as asocial physical practices, as mystical raptures of youth. The two young protagonists of the film, by no accident two cult figures from the cinema at the time, Pierre Clémenti and Jean-Pierre Léaud, are two modern saints who flee bourgeois expectations and the hypocrisy of their fathers’ generation. An equal amount of attention is dedicated to the merciless metaphorics of the film ›Salò or the 120 Days of Sodom‹ (1975), which reveals all kinds of power (political, economic, or religious) as violence against the body.

The exhibition concludes with a series of Pasolini’s articles that appeared between November 1974 and October 1975 on the title page of the most important Italian newspaper at the time, ›Corriere della Sera‹. In these articles, he called for putting the entire Italian elite on trial, pleaded for rebellion against all constrictions and control of the body, and called for the abolition of compulsory schooling and television. The series came to an abrupt end: on 2 November 1975 the media reported the news of Pasolini’s murder in the harbour of Ostia (Idroscalo) and the discovery of his corpse in the mud between barracks and garbage.

The exhibition concept seeks to present the steadfastness of the poet and the message that Pasolini tried to communicate in his artistic work with the help of original documents. In this context, a selection of original costumes from Pasolini’s films, from the cloak worn by the Madonna played by Silvana Mangano in ›Decameron‹ (1971) to the robes of the torturers in the most shocking scenes in ›Salò or the 120 Days of Sodom‹, will bring to life the poetry of his works, which were not only dedicated to stories of the oppressed. In Pasolini’s films, the costumes of the pioneering set designer Danilo Donati serve as banners of truth or ›embodied reality‹.

The exhibition ›Pier Paolo Pasolini: Porcili‹ reconstructs the systematic discrimination against someone who thought differently, someone who, despite all the time spent in courtrooms and the street attacks, censorship and mockery, wrote poetry and serenaded freedom and the body in his films and books.

The exhibition was curated by Giuseppe Garrera and Cesare Pietroiusti, with Clara Tosi as cocurator for the film costumes.