Oscar the elephant goes first. Alois the lion is second, followed by Leopold the giraffe. The three animals raise a rallying cry: »It’s about the children.« Soon, it is echoed by almost all the other animals around the world in Erich Kästner’s children’s book ›The Animals’ Conference‹. Written in 1949, in the aftermath of the Second World War when the horrors of the conflict were still both painfully fresh and not in the least understood, the book tells the story of animals who have finally had enough of humanity’s endless discussions, warmongering, dictatorships, hunger, suffering, and injustice—had it up to their snouts, trunks, and muzzles, once and for all.

»It’s about the children« becomes their mantra, quietly muttered, a guiding principle that gives them strength and resolve. So simple, concise, and irrefutable, yet so direct and beautifully honest that, despite any reservations one might have about Kästner’s book, it can still bring tears to your eyes today. Because, ultimately, it really is about them. Through no fault of their own, they are the passive victims of all the actions, inactions, and misdeeds of adults—both then and now. It is the children who are not only robbed of their present but are forced to see their future dismantled as well.

The phrase »It’s about the children« could just as well serve as the motto for ›BAUBAU‹, a large-scale permanent play environment set to open on 4 SEP at Gropius Bau. Designed by artist Kerstin Brätsch, the project spans three prominent exhibition rooms on the ground floor. It also puts children first. Its playscape offers kids a chance to »explore their own needs and interests«, as the museum writes on its website. Inside, trained playworkers are available to support the children, but not to direct them.

›BAUBAU‹ is to be a space for free play—a place where children can explore, whether alone or with others, let off steam, paint, build, craft, or do nothing at all. ›BAUBAU‹ could be described a safe space. Here, children are shielded from their so-called guardians’ dumb expectations, inflated ambitions, premature performance pressures, and all their overbearing projections. (And this, to be honest, also includes the above-mentioned notion that children are the future.)

»The children should have as much free space as possible, they should be able to let their imagination run free, to play, to act and to experiment«, says Brätsch. To paraphrase a canonical publication from the anti-authoritarian adventure playground movement of the early 1970s, one could say: it should be a place where »forbidding is forbidden«. For adults—meaning for us, for you and me, and likely for nearly everyone reading this text right now—the ideal, as articulated by the artist Palle Nielsen in a quote that also appears on the Gropius Bau website, is: »Perhaps children can tell us so much about their own world that it can also be a model for us?«

»The children should have as much free space as possible, they should be able to let their imagination run free, to play, to act and to experiment.«—Kerstin Brätsch

Nielsen is, in a sense, the godfather of ›BAUBAU‹: a Danish artist and activist who, in the 1960s, began transforming, guerilla-style, neglected lots and courtyards in Copenhagen into playgrounds with his like-minded peers. One whose approach—which sometimes clashed with the more orthodox views of his collaborators—eventually led him to partner with established art and cultural institutions to garner broader support for his ideas. In 1968, Nielsen and the journalist and activist Gunilla Lundahl launched ›Modellen. En modell for ett kvalitativt samhalle‹—›The Model. A Model for a Qualitative Society‹ in English—to great public acclaim: a project that converted the Moderna Museet in Stockholm into a creative play space for children. Young visitors were free to explore, whether alone or with others, to romp, paint, build, craft, or do nothing at all.

Nielsen’s project has long stood as a historical benchmark for the art world’s ongoing and increasingly intense focus on children and play, driven by a growing interest in inclusivity and accessibility. Among the most prominent examples is the ›Playground Project‹, led by urban planner and researcher Gabriela Burkhalter, which conducts historical research into playground design and architecture and has presented its findings in various exhibitions, including one at Kunsthalle Zürich in 2016. In fact, it was only recently that the Gropius Bau’s own ›Radical Playgrounds‹ came to a close, a project that transformed the institution’s forecourt into a gigantic outdoor playground in the summer of 2024. Curator Joanna Warsza, together with Benjamin Foerster-Baldenius of the Berlin-based architecture collective raumlaborberlin, invited a number of artists and art collectives to design play areas for children, but also offered a discursive programme for the adults.

The turn towards play in the visual arts is, in essence, not surprising; after all, experimental action and open-ended creativity are fundamental to both, and it is not without reason (albeit with a good dose of romanticism) that the artistic perspective is often likened to the supposedly unfiltered, more genuine view of a child. And yet, given the competing concerns around social relevance in the art world, it also offers an opportunity to reframe some core concepts that have recently come under scrutiny—including creativity, subjective expression and even the oft-criticised notion of autonomy—in a contemporary context. Play inherently involves a level of ›as if‹, a form of ›make-believe‹ that—unleashed within a self-contained, non-literal space—allows for ›consequence-free‹ exploration and experimentation. This safe zone, while detached from immediate reality, also serves as place for ›playfully‹ practicing relevant values of togetherness and the creative development of one’s own personality. Experiences gained through this process consequently have a very real, meaningful impact on day-to-day social behaviour.

As much as childhood—a phase that, since its invention, has per se been about the protected space of play, experimentation, and learning—epitomises these very values of freedom, independence and openness, biographical narrative might also frame it as a conditioning ›preparatory‹ phase for the perceived ›seriousness‹ of adult life. And as the visual arts and their institutions position themselves—with a nod to speculation, experimentation and open-ended exploration—as a much-needed haven for playful children in an age of pervasive pressure to perform, exploitation-driven optimisation and ever-shrinking spaces of freedom, it also offers an opportunity to encapsulate and preserve their own core values even as they recede from mainstream focus.

Utopia is not a climbing frame, but the chance to build one yourself.

But back to ›BAUBAU‹: like Nielsen and other proponents of anti-authoritarian playground design, such as KEKS—a Munich collective made up of art educators who designed numerous free play areas in the late 1960s and early 1970s and were invited to the 1970 Venice Biennale—Brätsch takes a ›loose parts‹ approach to her design: Rather than using prefabricated play equipment, which often at least partially dictates its use, ›BAUBAU‹ offers materials that invite active (and creative) engagement: cardboard honeycomb panels, balls, paints, tape, rolls, foam cubes and more. The floor is covered with paintable cardboard panels. Even the few fixed elements in the space are deliberately »abstract«, as Brätsch put it, and »could just as easily be a shop as a cave. It’s a multipurpose structure.« Utopia is not a climbing frame, but the chance to build one yourself. Future plans include incorporating natural materials such as clay and, where possible, extending the play area outdoors.

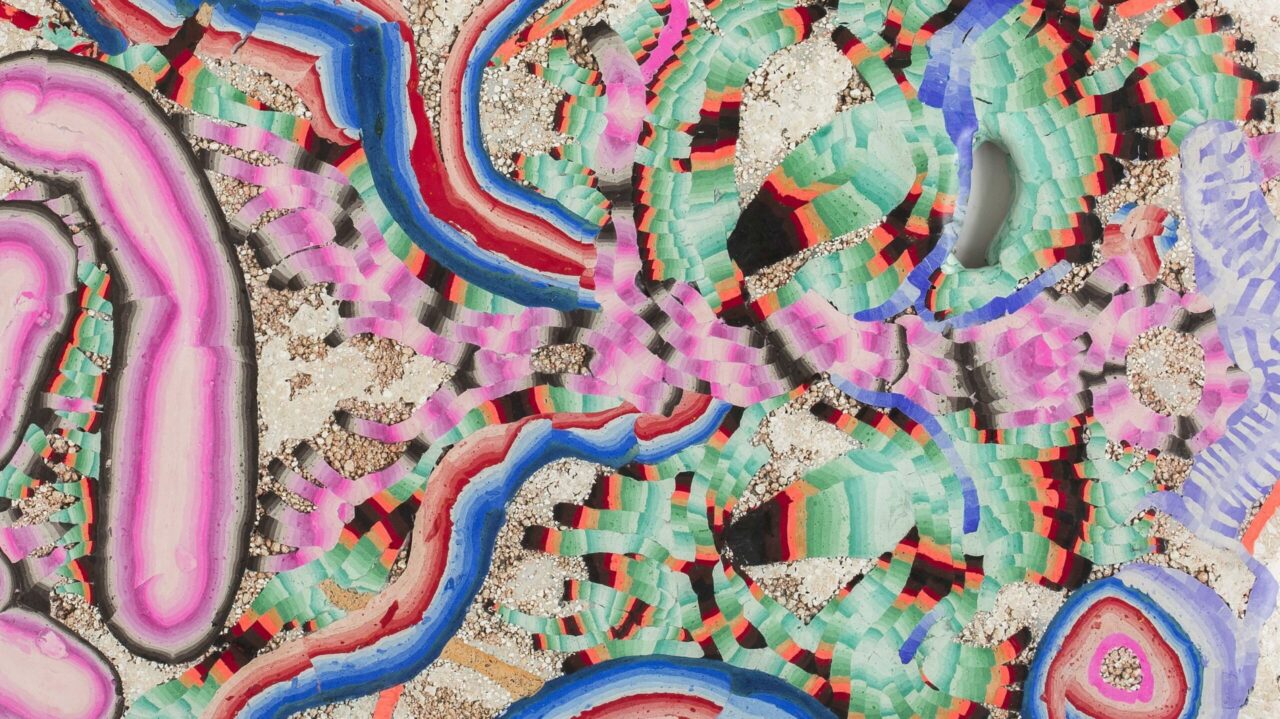

As much as Brätsch takes a back seat on the conceptual aspects, focusing instead on providing an environment and gradually adapting it to children’s needs throughout the project, the place itself unmistakably bears her aesthetic signature. Everywhere are the strikingly colourful abstract elements known from her work, the characteristic brushstrokes and marblings that, at times, seem to take the form of strange characters, not unlike a Rorschach test. There are dinosaurs to be found here—so many children’s prehistoric favourite—the very creatures that merge and fuse the fantastical dragons of their imagination with reality and often give kids their first real sense of the unfathomable depths of time. In any case much of the space feels surreal, oddly animated, and alive, balancing on the edge between the abstract, the ornamental, and the representational. Nevertheless, as Brätsch explains, it is »clearly a space for use«. »Even though I designed it, it’s not an artwork. It’s much more like an extension of what I do as an artist.«

Expansion and absorption, as both a strategy and a practice, feels central to Brätsch’s conception of art, vital for her approach and her projects. Starting from her core medium of painting, Brätsch—who returned to Berlin at the end of 2020 after a decade and a half in New York—has developed a sprawling, meandering oeuvre over the course of almost 20 years: an ever-branching corpus, one that devours itself only to spit it right back up, many-headed and multi-bodied, often emerging in collaboration with other artists, be it Adele Röder in DAS INSTITUT or Debo Eilers as KAYA, to name just two of the most prominent projects. The artist herself refers to this process as »metabolism«.

Brätsch’s name, then, was quick to come up in art discourse from the mid-2000s onwards, whenever ›expanded painting‹ was brought to the fore. The term referred to an art form that, against the backdrop of a largely digitised dissolution of boundaries and dematerialisation, understood painting as a dispositive for addressing questions of expression and subjectivity, circulation or commodification with the simplest of means and in the form of a supposedly singular, yet networked and interconnected artwork-as-object. As noted in the announcement for Brätsch’s major survey exhibition at Munich’s Museum Brandhorst in 2017, »Kerstin Brätsch’s pictures reflect the pressure to which the medium of painting is exposed by the increasing dominance of digital technologies«—a reflection of the zeitgeist of the ›post-media‹ discourse prevalent at the time.

Brätsch has developed a sprawling, meandering oeuvre over the course of almost 20 years: an ever-branching corpus, one that devours itself only to spit it right back up, many-headed and multi-bodied, often emerging in collaboration with other artists.

A lot has happened since then. Discussions about the differences between media, whether laden with countless ›post‹- prefixes or half-ironically, half-helplessly dubbed ›zombie painting‹, are no longer the draw they once were. With the benefit of hindsight and, consequently, the uncertain perspective of historical proximity, these conversations may easily appear as the last gasp of a modernist conception of art and one of its core concepts—the ›medium‹—before a major paradigm shift redirected focus towards more activist, political and infrastructural thinking.

Brätsch herself has long widened the scope of her ongoing exploration of painting to include a study of practices related to artisanship and craft. With the help of skilled artisans, she works with techniques such as marbling, a craft traditionally used in bookbinding, and stucco, which has been used for centuries to create deceptively realistic imitations of marble: methods that, incidentally, serve to artificially imitate the natural. During a visit to her studio, which is currently also located in Gropius Bau, she points to recent works where she has ›fossilized‹ her distinctive multi-coloured brushstrokes—isolated and refined them over time into a kind of ›signature style‹—in the form of a stucco.

It is hard to imagine a more incisive, confident, and reflexive way to engage with the tools that painting offers today: the individual brushstroke, once the ultimate seat of the subjective in art, congeals into a rigid, pure form, becoming what Adorno might call a »formulaic phrase«, as the philosopher described the characteristically detached, jagged and turned-out elements in Beethoven’s radical late work that refer only to their own formulaic nature. Life doesn’t simply go out or slip away here; instead, it is virtually exorcised through a renewed act of subjective expression—with the formulaic phrase employed as, to quote Adorno again, »monument to what has been, marking a subjectivity turned to stone«.

Interestingly, and parallel to her own artistic practice, Brätsch has increasingly taken on design commissions in recent years, consciously working in an ›applied‹ arts vein within the context of these commissions: a cafeteria at MoMA in New York, an iridescent floor mosaic in the outdoor area of the new Luma building in Arles, another café in the rotunda of the Fridericianum in Kassel—and now ›BAUBAU‹ at Gropius Bau. To put it somewhat provocatively, one could argue that as Brätsch pushes painting as ›pure‹ art into a state of petrification and stasis, she breathes new life into it through applied or more functional designs for communal spaces such as cafés and, now, a playground. The future belongs to what is needed and what finds practical use.

To conclude that the endless ›game of painting‹ has finally come to an end would not only be presumptuous, it would most certainly also be wrong. But who knows, taking an artistic practice as thoughtful and precise as Kerstin Brätsch’s as an indicator or seismograph, perhaps it is true and painting is indeed turning to stone. Rigid and disconnected, then, its individual elements lie scattered like the bones of a decaying dinosaur skeleton—here a brushstroke as long as a brontosaurus femur, there a colour gradient as powerful as the mighty skull cap of a triceratops. Whoever discovers and excavates them in the distant future may marvel at how different, strange and unimaginably fantastic these remains are. But who will that be? Who will come to excavate the painting? Alien creatures from other worlds? Artificial intelligence from the depths of our circuit boards? Well, perhaps more likely it will simply be the children, those humans of the future.