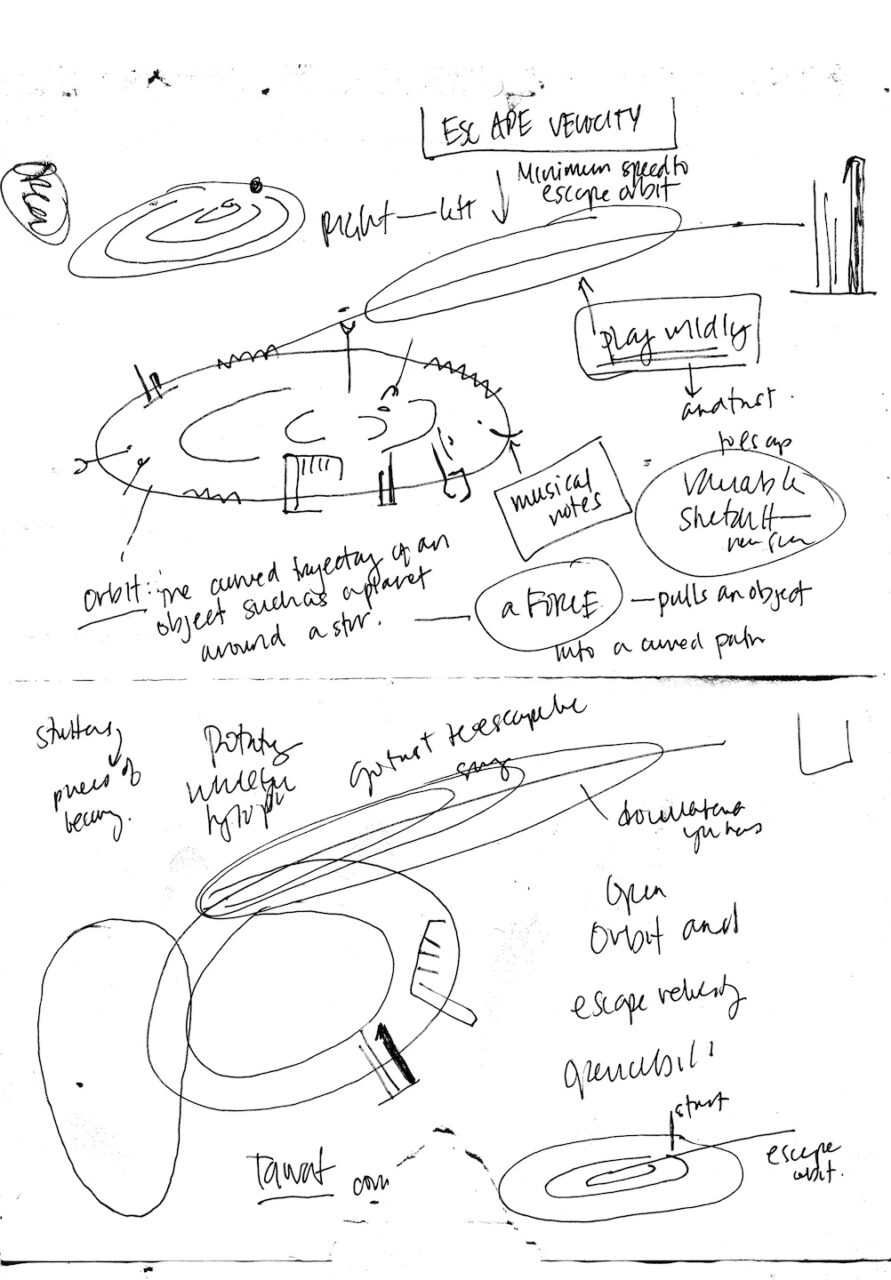

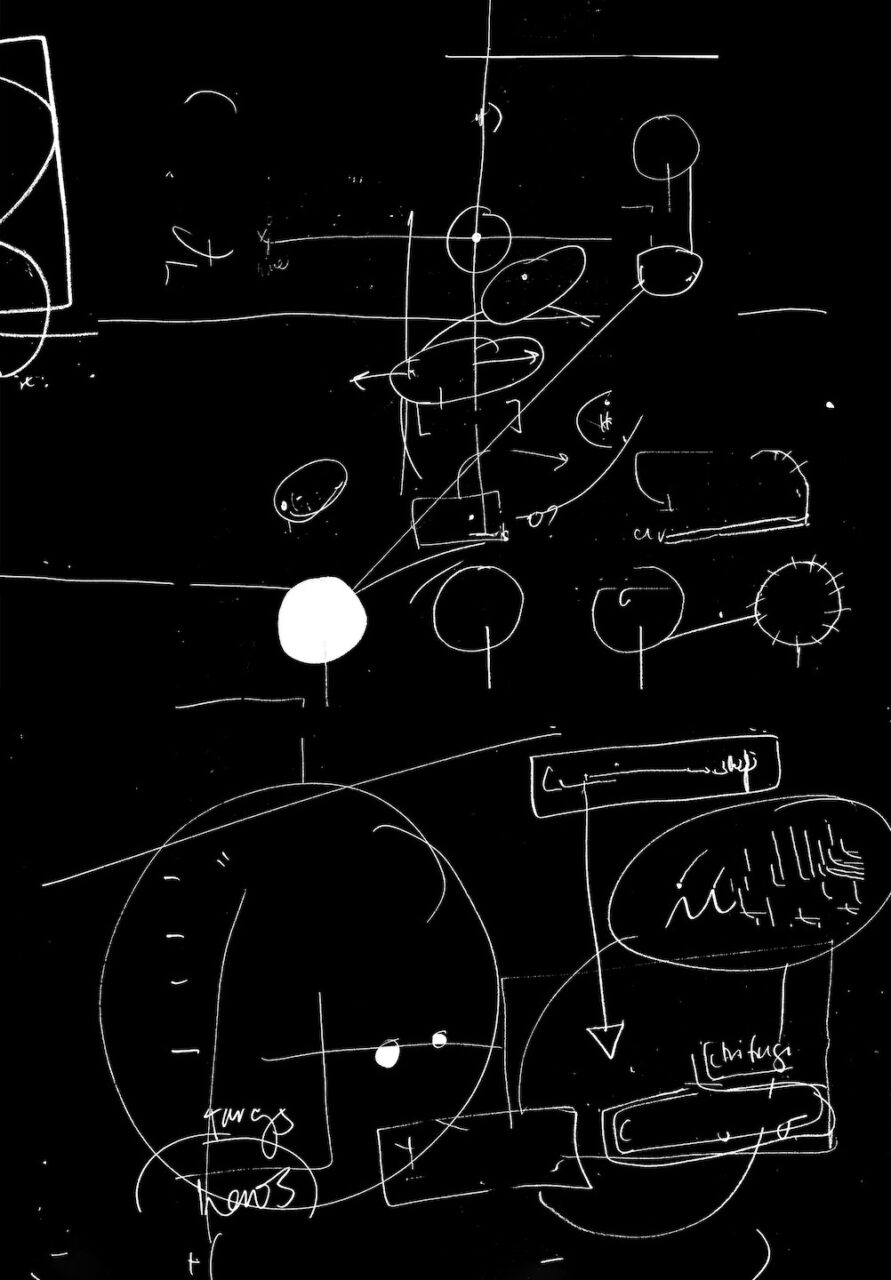

Kameelah Janan Rasheed describe themselves as a learner. Their text-based works—rarely finished, constantly taking on new forms, being commented on and expanded—question ways of knowledge, tap into the invisible, the unsaid, showing a lot of joy in moving and learning though language play. In 2022, Rasheed received the Schering Stiftung Award for Artistic Research. The award is accompanied by a solo exhibition at KW Institute for Contemporary Art (KW), which will open during Berlin Art Week. Throughout our conversation, Rasheed makes notes and sketches that are reminiscent of their works: geometric shapes, connecting lines, words, scraps of thoughts.

Carolin Schmidt (CS): »Every story I create, creates me. I write to create myself«, says author Octavia Butler. How do you see yourself as an artist, researcher, creator? Do you create and recreate yourself every day?

Kameelah Janan Rasheed (KJR): When I first started making work, it was explicitly autobiographical. I wanted to talk about myself and my family in the context of displacement and archival practices. More so now, when I make a work or plan an exhibition, there is a question or something that is making me itch a bit and the exhibition is a way to engage in a public learning process. It would be impossible for the processes of making and revising not to change me as an artist and just human in the world. The upcoming show here at KW changed the way that I look at exhibition timelines and communication with curators.

CS: The curator of your show, Sofie Krogh Christensen, revealed to me the title of the show—›In the Coherence, We Weep‹—and that the exhibition is very closely interconnected with an artist book you are doing. How are the two connected and could you tell us more about the title?

KJR: There were several times when we asked ourselves how we could make a book and design an exhibition at the same time! Sofie visited New York in March, and we literally sat at my living room/studio table for four or five hours, just talking, writing, reading, pausing, and moving around. And every week since the top of the year has been sprawling conversations. The aspect that feels part of everything—from the creation of the book to the production of the show—has been the development and sustaining of long-term relationships with both people and space. What does it mean to develop intimacy with people and objects—the book being a transportable object, that expands the exhibition. And about the title, ›In the Coherence, We Weep‹—in my book ›No New Theories‹ there is a section that reads ›In the Coherence, We Weep‹. I will say that a lot of times I write, I do not have an immediate understanding of what it means or a goal. Sometimes it is almost like an intuitive reaction to a lucid dream, the texture of a piece of text, or other stimuli. I see the letters and I want to combine the letters in a particular way.

»What I have learned about learning is that it doesn’t happen in isolation.«

CS: The catalogue for your show at Kunstverein Hannover features a long and intimate conversation with Legacy Russell. I especially loved the hints and notes you added after the interview, kind of a retrospective comment on the talk. It seems to be an interesting way of laying bare the process and reopening the dialogue.

KJR: Being a high school teacher really shaped the way that I think about reading and writing. There is so much pressure for kids to read something for the first time and then immediately understand it without returning to it. One of the things I was really proud of as a teacher was spending time with one thing as long as I could. What does it mean if we develop intimacy with this one text? What does it mean if you keep coming back to your essay to revise it? And so, if I approach my own writing and reading practice, I want to know more about the innards of a process and I want to make that process more visible. We have done that for ›No New Theories‹, too, which I talked about before. There was an error in the print, and we thought: »What if we lean fully into the idea to revise publicly?« There is no reason to be ashamed when something doesn’t turn out as you thought. You should be changing all the time. Legacy Russell wrote one of the very first essays about my work in 2013. When I asked her if she wanted to do this interview, I was excited for someone to revisit my work ten years later. That is a privilege for me. There is something about moving in and out of the focus throughout the interview which felt really lovely.

CS: Is there an aspect to knowledge that you think is specifically important to you and your work?

KJR: What I have learned about learning is that it doesn’t happen in isolation. You may read a book by yourself and write an essay, but between that time you read that text, and you write the essay, you talk to people; you have a series of encounters that you don’t think are going to impact your writing, but they all do. This idea of mastering the world individually seems odd to me. I am trying to invite people to be okay with uncertainty and collaboration. Not just as a fashionable aesthetic but as a fact of life.

CS: And still, it seems like your work holds many ways of offering different incentives to the viewers—intertext, hints, associations. Maybe this is a bit of a technical question, but how does your archive look like? Do you have a special systematic to it?

KJR: Most people think that I am really organised and that I have a specific system. But I have a tense relationship with taxonomy and the ways that things are organised. I think the labels you put on things determine what is discoverable and ultimately, what becomes visible. In my home archive, I know where things are. But if the public were to enter my archive they would be lost. I have found a lot of joy in that for a couple of reasons. The first archive I engaged with in the traditional way was at the California Institute of Technology, when I was an undergrade student. I was doing research on eugenics—everything was organised perfectly. I began to wonder if I had just been given a box of stuff and had to find what I wanted, would I have encountered what I think I wanted in that process? The notion of chance and serendipity is very important to me.

CS: I am curious—anyone whose work you admire?

I have been obsessed with Gertrude Stein lately. There is one purple book by Stein called “How to Write” that I brought with me. It is such a beautiful text! The introduction mentions if you were to open any of Gertrude Stein’s works, you would be confused and ask yourself what this is. That is the way that I imagine archives to be—not about me directing where to go, but as a world that opens for you to make your way through it. I find Gertrude Stein absurd in ways that feels necessary, at least for me in this moment of reconciling my relationship to absurdity, logic, and certainty.

CS: I also admire her work. You can read a sentence a hundred times, for example »The difference is spreading«. Then you close the book and you come back at a later point, and it can mean something completely new …

KJR: … yeah, but none of the letters on the page have moved. There are in the same place. But you keep re-encountering them differently and reading them in a different context. In her book ›Tender Buttons‹, there are some excerpts of articles reviewing her work and she talks about the notion of beauty and acceptance. Specifically, she mentions how everything is understood as ›ugly‹ until someone else does the same thing and then they become known for the thing you were disparaged for doing … Also, from the excerpts, it seemed that people were frustrated with her lack of transparency—I like that, too (laughs).

»When I think about knowledge, I like to think about the experience you have with your body.«

CS: Lack of transparency can be a form of resistance. Are there other poets you love and is Black storytelling especially important to you?

KJR: I just remembered how I arrived at Gertrude Stein—I came to her through Harryette Mullen’s two texts: ›Trimmings‹ (1991) and ›S*PeRM**K*T‹ (1992). My first encounter with Stein made me say »Oh, this woman got this published!? This is nonsense!«. But then I found that I liked the nonsense. And I started to understand this nonsense or maybe enjoy misunderstanding it … There is a way of responding to someone’s work by writing an essay about it, but I think Harryette Mullen’s poetic annotation, intervention, and interweaving is quite beautiful. I love the work of Douglas Kearny, too. He does a lot of work that I believe he and others have called ›performative typography‹. He works adjacent to concrete poetry practices and at times it almost feels like music notation—it is very graphic and diagrammatic—it moves. I also really love Emily Dickinson, which everybody seems surprised about. I think that occupied the space of being perceived as this annoying and inconvenient woman. I might be drawn to so-called annoying and inconvenient women in history (laughs).

CS: Earlier on you talked about different ways of gaining knowledge and speaking of nonsense and meaning. I wonder what knowledge means to you and how it affects your artistic research and work?

KJR: There was a time in my life when I thought knowledge was this concretised form and it becomes part of you because it’s an object that you can absorb and take in. The more I learned, I recognized that most of what I’m doing is trying to chase some ambient or non-solid thing that doesn’t want form. Things are constantly changing and the form to hold something steady is not the form that something most desires (laughs). When I think about knowledge, I like to think about the experience you have with your body. The knowledge that will be produced when people go through an exhibition by choosing a certain pathway, or by taking the stairs up and being slightly winded by the time they get to the next floor and how that impacts their sense of space. I think about knowledge it in a very experiential way. I could tell you about the space, I could paint you a picture of the space, I can make you listen to an audio lecture—but there is a sense that you must feel this with your own body. There is a poet whose work I also love—Asiya Wadud. She has a poetry collection called ›No Knowledge Is Complete Until It Passes Through My Body‹. As she notes, the title comes from The New York Times story about Congolese choreographer Faustin Linyekula who states, »Where I come from […] no knowledge system is complete until it goes through the body.« I’m thinking a lot about the body. Even though the show has no figurative bodies, the body is there. The body is the people who show up and wander through the space.

»I desire cultures of play and leisure in both its frivolous and its non-frivolous elements.«

CS: Sometimes we are really driven by the idea of understanding and making sense. Do you think that art can encourage people to listen to their bodies, to embrace the unknowing?

KJR: I hope. We are always trying to get to the next experience. But I think that there is something to be said about spending a lot of time on one thing. There is an interest in me, trying to design experiences that invite people and reward people for coming back for multiple reads. We’re driven by a sense of fulfilment and reward. So, by not providing a clear, coherent understanding of something, the reward must be something else. So, the question becomes—what am I offering? And I think I offer a relinquishing (laughs) or distancing from that desire. If you are just trying to reach the destination, you will miss a lot on the way. I desire cultures of play and leisure in both its frivolous and its non-frivolous elements. You should be able to have frivolous fun and structured pedagogical fun.

CS: Together with the artist Diederik Brackens you were interviewed by the Poet-in-Residence at the Guggenheim Museum, Taylor Johnson. There you talk about pain being a part of the learning process. Does learning have to be painful?

KJR: (Pauses) Yeah, I had a student ask me this question once. I always lectured about fun and joy and the pleasure of learning. And I told him »Yes, unfortunately, it can«. I’ve learned so much through terrible things that have happened in my life—I just think that it is encoded differently. The emotional attachment is different when you have to learn something in a difficult way versus a fun way. Like when someone taught me how to do a ›Half T in Horton Method‹, which is a dance position—that was fun. When I think about understanding notions of displacement and losing my family home—that is not fun. But I have this new schema of understanding displacement and space in this architecture because of this experience. I wouldn’t have been able to do this show without a certain context, without having the learning that came from not having my own space for a decade of my life and then moving through these moments of interrogating what it means that some people have access to this space and other people do not. That is part of the ›How to Suffer Politely (and Other Etiquette)‹ series, too—there is a large expectation that people who had extreme experiences of suffering find some way of turning it into a jaunty tune or make it entertaining or complain in a way that doesn’t make people uncomfortable. Not everything you learn is going to be something that makes you feel good. I often wonder what it would look like to live in a world, where suffering does not have to function as a base, where suffering is a thing that we experience generally, but it is not the base for an identity or a conceptualization of the world. And I think that part of what I am saying is not so much that I want to linger in the suffering—I want to think about how we got there and how the ways in which we discipline and how people express their pain only replicate the pain because you are not actually allowing for people to release and do the things that are constructive for them to process it.

CS: This reminds me of Toni Morrison’s idea of ›rememory‹ that she talks about in ›Beloved‹ for something we have never known, as something we have forgotten and thus makes the historical past a part of one’s own experience. Do we have to see things from a different point of view? The Western art world is mainly focused on a white perspective—do you think art can also be a way of creating new centres?

KJR: Yeah, and I think we talked a lot about centres for this show, too, because we were really interested in what architectural features are given the most attention and which ones are neglected. I’m curious about celestial mechanics and orbital structures, especially escape orbits or when an object has attained enough directionality and speed or velocity to escape the orbit of a mass that holds gravitational influence. I’m not interested in creating more centres because I think that the thing that happens when you create another centre is that people feel pulled to engage in the methodology over there at the cost of some type of alternative way of being. I think art creates a bunch of centres and orbital pathways all the time. I am really interested in what would happen if there was no centre.

CS: The ›Spirit‹ series that was on display at the Kunstverein Hannover last year seems to work around those ideas. You used a lot of abstract photos to create organic movements, circles and black and white contrasts, almost space-like. There is this aspect of repetition and variation in your work. In ›Punctuated Blackness‹, ›and, Black?‹ and many other installations, too, the way you repeat words feels like a meditation, almost like a hymn. Can writing rituals and artistic practices be spiritual?

KJR: Yeah, I think about spirituality and rhythm a lot because, as a Muslim, our day is divided into these sets of repeated actions. We pray five times a day. We also do ›dhikr‹. There are all these specific moments where there is repetition. Being a kid, I was like—why do we keep doing the same thing every day all the time? We already did it once—what’s the purpose? As I got older, I realized that you are repeating the same words and engaging in the same bodily motions. But each instance that you are doing it, you are a different person, you are encountering different versions of yourself. And so, the repetition becomes almost like a vessel to hold a certain possibility for expansive experiences. By engaging in this particular set of repetitions, I now have a container for the possibility of experiences. As much as I don’t like centres, there is something really important to me about being reminded of an expectation around a certain set of rituals as an offering. I think that is where repetition comes in for me. I don’t know what is going to happen when I repeat something—repetition creates a rhythm for possibility.

CS: You have already said that an artist should not be in an orbit of their own. What do you think of art as a collaborative process? And how could you imagine it to be? How do you imagine an artistic utopia?

KJR: I think all utopias are doomed to fail (laughs). The city I grew up in started as a town that would become an agricultural utopia under Charles Weeks. And then it became a town that allowed for Black folks who were not able to buy property in other places to be able to move there and start a life. It also then became a place where people experimented with the idea of how schools could form. So, I have learned about all these different iterations. I am very interested in notions of utopia and hyper-intentional communities. If I were to even approach the idea of utopia, it would be like the notion of being because utopia is like no place—it doesn’t exist. I think that I would love an art future where artists felt safe, comfortable, and encouraged to make whatever they wanted. I want a future where people are okay to get more weird.