Think of them as the circular ripples that form on the surface of a lake when a pebble is thrown into it, only much more powerful and on a far grander scale: gravitational waves are created, for example, when two black holes in the universe orbit, collide, and eventually merge. These cosmic events are so powerful that they warp, compress, and shift the very fabric of space-time, much like the motion induced in water molecules by the force of a pebble. The resulting changes on Earth are minuscule by comparison, so much so that for a long time they remained immeasurable. But in 2015, researchers at the US-based Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) succeeded for the first time in converting these gravitational waves into acoustic signals. It was a scientific breakthrough, a sensation that not only confirmed the existence of these waves, but also provided compelling evidence for Einstein’s theory of relativity.

In the words of artist Annika Kahrs, »What was once invisible to us is now something we can hear. We’ve effectively been given ears.« It is »insanely poetic«, she says, that something so incomprehensible and naturally imperceptible has been made audible. Audible, verifiable, yet almost incomprehensible, particularly for those of us without a degree in astrophysics. The headline-grabbing sound of those gravitational waves had travelled a staggering 1.8 billion years to Earth.

»Sounds, soundscapes, and music have always been a key source of fascination for Kahrs, both personally and as an artist. Music as artistic material, as a means of communication. Music as structure—also as a symbolic representation of social systems.«

It is this very sound that forms the basis of Kahrs’s latest work ›Gravity’s Tune‹, a sound and video installation on view at the Schering Stiftung to coincide with Berlin Art Week. Kahrs has been working on the project for three years and filmed it in the United States, where the research facility is located. Production took place during Kahrs’s residency at the Villa Aurora in Los Angeles, albeit with several delays due to repeated postponements caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Surprisingly, this did have an upside; it gave Kahrs extra time to reflect on her concept, strengthen ties to scientists and seek additional funding. When we spoke at the end of July, the artist was deep in the editing phase—an odd time, she says, to be discussing her work. As Kahrs herself put it, »A lot is decided in the editing process; this is where you really start to understand what it’s going to be in the end.«

Annika Kahrs is not a scientist. Born in 1984 in Achim, Lower Saxony, she studied, among other places, at the University of Fine Arts in Hamburg and the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna under professors such as Andreas Slominski, Jeanne Faust, and Harun Farocki. Sounds, soundscapes, and music have always been a key source of fascination, both personally and as an artist. Music as artistic material, as a means of communication. Music as structure—also as a symbolic representation of social systems.

Kahrs first came to prominence with ›Strings‹, a work created in 2010 when she was still a student. Like so much of the artist’s work, it exists in dual form, encompassing both a live performance and a video. The piece shows a classical string quartet playing, or rather attempting to play, Ludwig van Beethoven’s Opus 18 No. 4 in C minor from 1800, taking on ever-changing roles. After the first movement, the musicians stand up, change places and instruments, and continue the process until they return to their original positions—and until harmony dissolves into cacophony and nervous laughter. The work is prototypical of Kahrs’s approach. Her aim is to create moments of confusion, new connotations, to induce shifts in perspective, »to shift a bit the things we’re used to«. This is often enough »to reveal some of the underlying structures, like a set of building blocks where things have to be rearranged«.

»What does a gravitational wave sound like?«

Kahrs uses these shifts and rearrangements to create performances, sound pieces, and videos that are not only arresting, acoustically and visually, but also rich in multiple layers of meaning. Music or sound always serves as a starting point for Kahrs, but never as an end in itself; instead it becomes a means of exploring various social, societal, political, or scientific facets. ›The lord loves changes, it’s one of his greatest delusions‹ (2018) engages both a chorus of whistling performers and the drawn-out sounds of a pipe organ; the piece deconstructs the melody of Luther’s hymn ›A Mighty Fortress Is Our God‹, the most important protest song of the Protestant Reformation. ›Infra Voice‹ (2018) finds Kahrs plumbing notes almost too low for the human ear, attempting to communicate with a giraffe with the help of the rare octobass instrument. For her contribution to last year’s Lyon Biennale, meanwhile, she probed the history of Lyon’s silk weavers through sound and music.

What fascinated her most about the acoustic translation of gravitational waves, says Kahrs, was that it was a completely new and remarkable discovery, one that came at a challenging time for science. So what does a gravitational wave sound like? »Relatively unspectacular«, says Kahrs. She describes it as a ›chirp‹, a rapid rise followed by a fall, lasting just two seconds. It’s a sound with no particular musicality, not inherently beautiful, but full of information that has the potential to profoundly alter our perception of the universe. This is Kahrs’s starting point, where she begins an attempt to fathom it.

»We do the same thing in art; we don’t explain our work, we translate it. We take insights or systems as a starting point and reflect on them, find images, a translation—maybe even poetry.«—Annika Kahrs

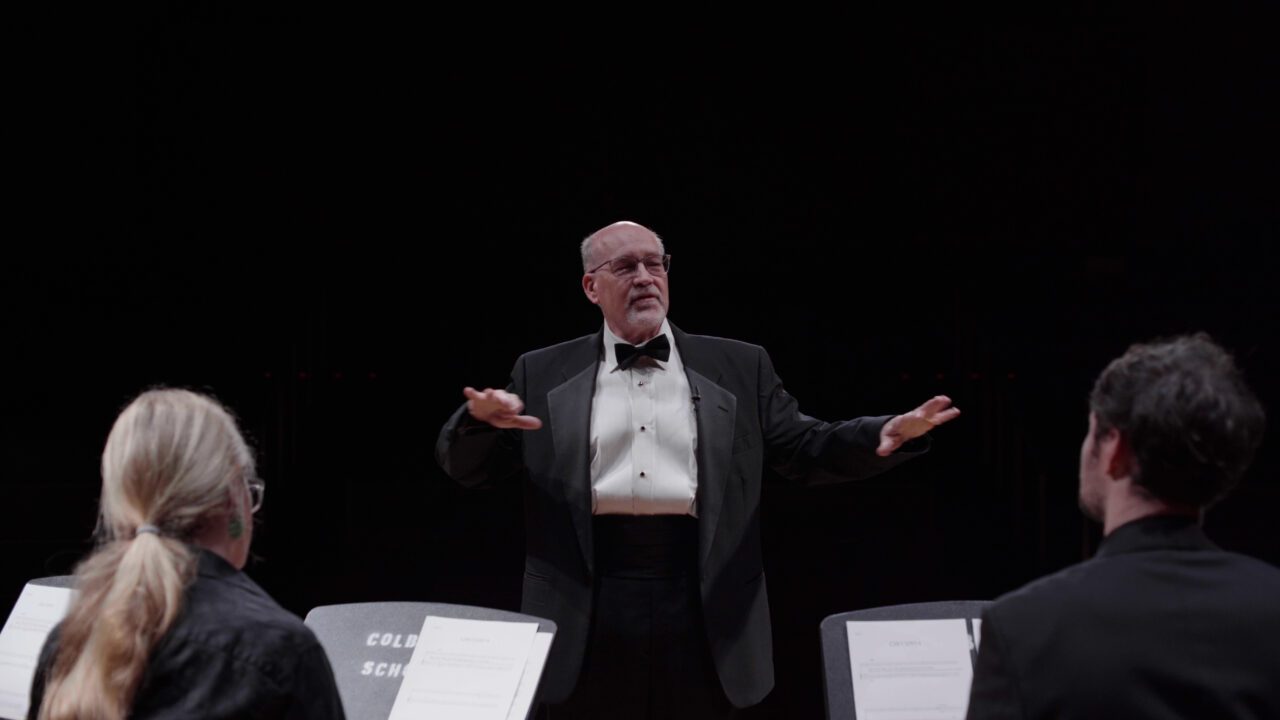

Crucial in ›Gravity’s Tune‹, the artist emphasises, is the aspect of »note-finding or working out a piece of music«. To do this, she sought the collaboration of Louis d’Heudières, a composer with whom she has worked for many years. D’Heudières transformed the scientifically translated acoustic signal into a musical arrangement, providing a translation of the translation, so to speak.

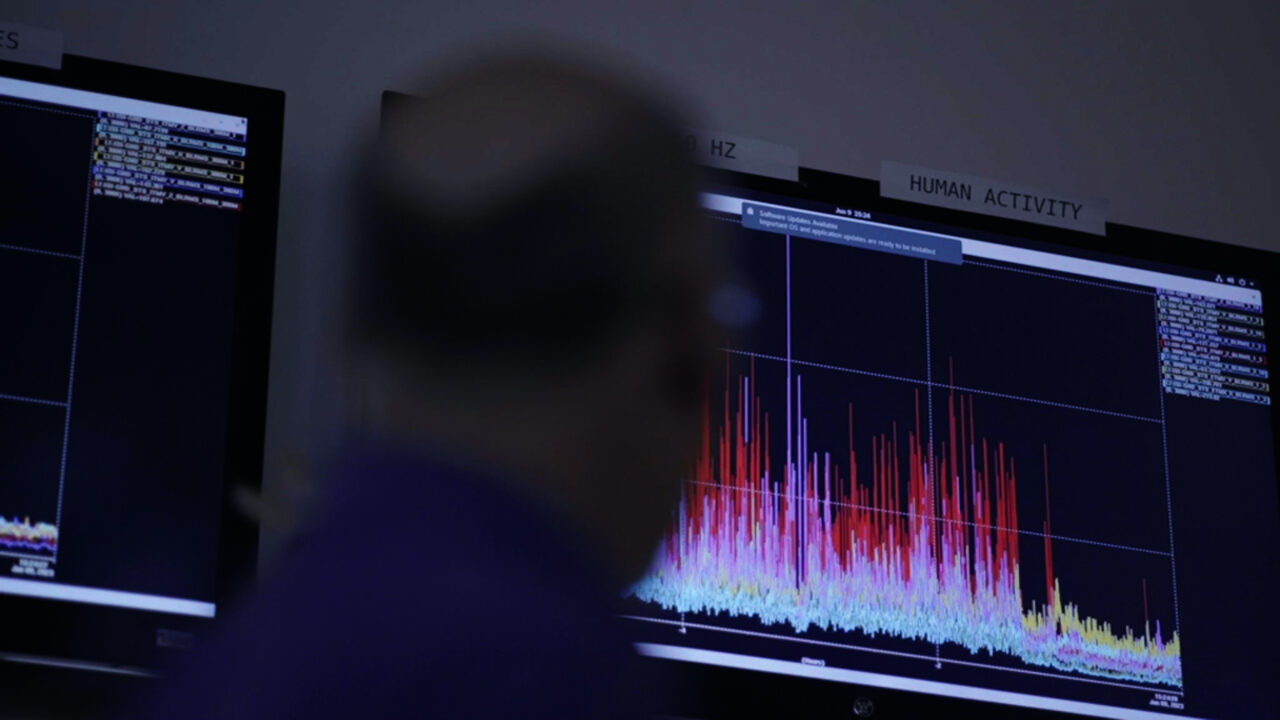

In her film, Kahrs blends two levels: on the one hand, a twelve-piece musical ensemble working on and with the composition, lively and engaged in discussion; on the other, the concentrated quiet of the scientific facility, the LIGO control room, affectionately dubbed »the world’s quietest concert hall« by researchers. Kahrs skillfully navigates the interplay between science and music, exploring both the musical possibilities of scientific discovery and the information and knowledge embedded in and conveyed by music.

This is also where she sees a kind of overlap between disciplines, between art and science—in those very same mechanisms of translation and interpretation. »We do the same thing in art; we don’t explain our work, we translate it. We take insights or systems as a starting point and reflect on them, find images, a translation—maybe even poetry.« Annika Kahrs certainly finds that.