This article first appeared in the Berlin Art Week 2025 special issue of Freitag.

Not unlike the skin of a sausage, the outer layer looks ready to burst as it stretches over the feathers. For now, though, the down jacket holds its shape, still gleaming in the light as if it were a precious treasure. With each glance the puffed-up garment becomes more like a suit of armour, deflecting reality at every turn. But it is not made of metal, even if its sheen suggests otherwise. What once promised protection could rip apart in the very next moment.

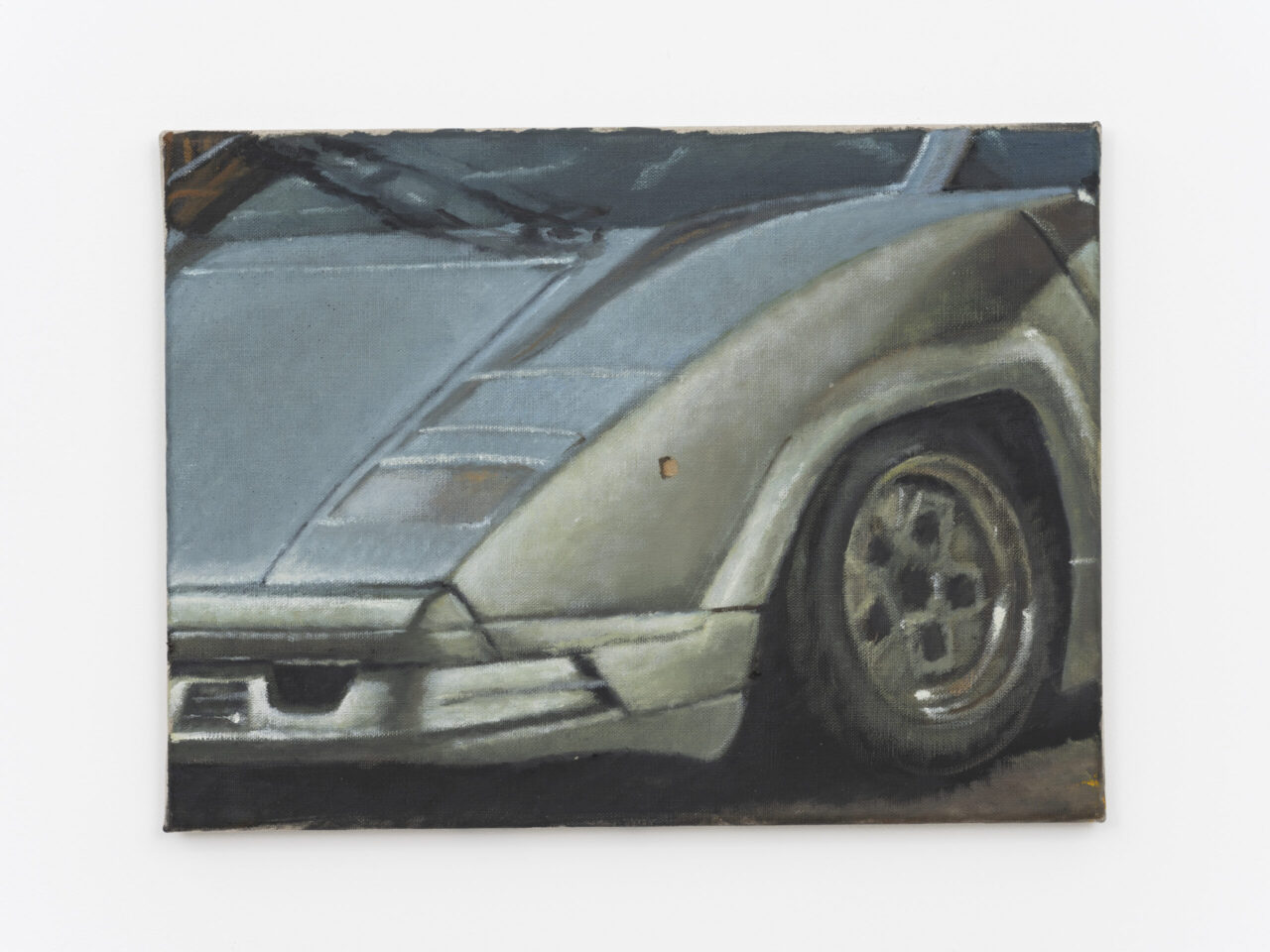

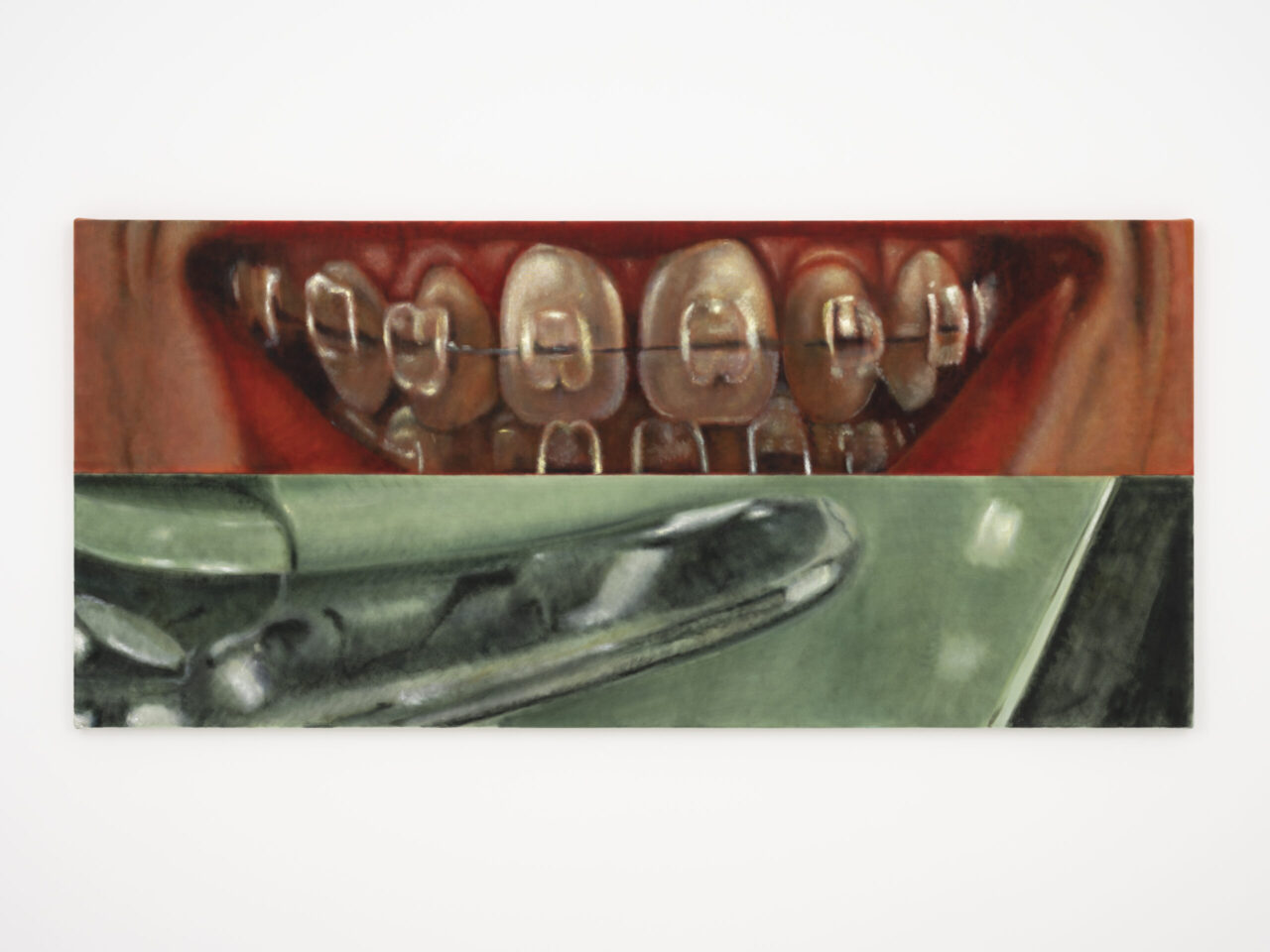

How the familiar and the longed-for can become strange under prolonged observation—how not only things themselves change, but also our perception of them—all this is very much of interest to Issy Wood, the London-based artist born in 1993. Cola cans, dental braces, leather car seats, pumps covered in fur: in her art, these objects appear uncanny, removed from the surroundings that produced them and, at the same time, oddly reconditioned. The everyday seems distorted, displaced, at times unsettling—and in precisely this weirdness, deeply desirable. »Weirdness is difficult to describe,« Wood admits. »I guess it’s seeing or hearing something in the wrong place, and having to reassess what you thought normal was. I think a lot of art isn’t weird enough, and that includes my own. Truly weird things don’t even know they’re weird.«

»I’m a young millennial and, for better or worse, come from a generation that took a photo of a sunset before actually looking at that sunset.«—Issy Wood

Commodity fetish and excess

Wood’s smeary, dark paintings—bearing titles such as ›Slouching towards the maxillofacial unit‹ or ›Bulimia moodboard‹—are now on view at Schinkel Pavillon in her first major solo exhibition in Germany. Its title is ›Magic Bullet‹, and strictly speaking what is shown there are images of images. The motifs Wood paints come from a trove of screenshots on her iPhone. She selects the fragments, frames them, and within that frame surrenders to a kind of looking conditioned by the smartphone. »I’m a young millennial and, for better or worse, come from a generation that took a photo of a sunset before actually looking at that sunset,« Wood says. »I’m used to that level of mediation. I’ve tried to paint from life before and I didn’t enjoy it, perhaps because I now crave the edges of a crop, and my own field of vision doesn’t ›end‹ clearly enough.«

The notion of the end plays out on multiple levels in Wood’s practice, which has been described as at once surreal and hyperreal. Her cropped images bring what lies outside the frame to the fore. The works circle around what is hidden, lost, unspoken, contradictory, and macabre, drawing on the signs of a late-capitalist society. They conjure a bleak, nightmarish world suspended between commodity fetish and excess, one that appears—if not already lost—then at the very least sunk in a depressive state.

Wood’s photorealistic oil paintings may seem anachronistic and grotesque at first glance—perhaps because they bring together consumer culture and Dark Romanticism with a touch of irony. »We can learn a lot from Goya about how to make the most of a mental breakdown or intense paranoia. His ›Black Paintings‹ are a key example of this,« Wood says, adding: »Goya was also very, very funny. The captions he added to his etchings almost seem to have predicted a medium like Instagram. Sometimes I look at the Old Masters and think how little has changed. We are all still obsessed with wealth, status, beautiful women, clothing, desperate to make sense of the world through allegory, religion, or myth.«

Amused by her own fascination with the Old Masters, she once jokingly called herself a »medieval millennial«—a label the US-born painter, musician, and avid blogger has never quite shaken off. She studied art because the entry requirements were less demanding than for other subjects, and her grades were enough to secure a place at Goldsmiths, University of London. From a young age she struggled with depression and other mental illnesses, with long stays in clinics disrupting her schooling. Because of her body dysmorphic disorder, a disorder of body perception, Wood dislikes being photographed. She began painting self-portraits so she would not constantly have to pose for magazines and newspapers. Masks, hands, spectacles and glasses conceal her face.

In the exhibition at Schinkel Pavillon, it is, fittingly, a keyboard that now obscures the artist’s body—Wood has released several indie pop albums to date. She has turned down not only mega-gallerist Larry Gagosian but also music producer Mark Ronson, preferring to set the conditions of her work herself. Defiance, refusal, and rebellion are words often attached to her in the press, and at the same time they feed into a kind of self-staging on the art market, where whatever resists is all the more in demand. Yet this role sits uneasily with the reserved Wood: »There is always a shock when I see a painting of mine anywhere except the studio. It feels like running into a teacher outside of school.«

While Wood paints alone in her studio, she collaborates when making music. Working artistically with other people, however, remains a challenge for her. With a touch of sarcasm, she remarks: »I’m awful at it. I’m starting to try it with music. I’m used to being alone, I’m used to blaming myself when something goes wrong and celebrating myself when something goes right. It’s probably why my personal life is a mess.«

»I try to capture that feeling of not fully knowing where you are in space and time in my work. This might not be melancholy, maybe disorientation. My inner world is much less poetic than melancholy.«—Issy Wood

Wood updates a blog more or less regularly with short texts. Poems, stories, anecdotes about quitting smoking (and starting again) appear there, alongside reflections on her creative processes. Some of these posts even find their way into the lyrics of her songs. The most recent entry sets a maths problem: »Take the number of times you’ve been in love, divide it by the number of times you’ve been in lava. (…) Divide it by the square route of your Seroquel dose, and multiply this by the number of women under 50 who’ve betrayed you and the number of minutes it’s been since your last piece of hate mail. Divide it by 2 because a problem shared is a problem halved, then double it because this isn’t true in the slightest.«

Comedy and pathos, delusion and critique—these hold together the disparate elements that in Wood’s art stand side by side, like tabs left open on a screen. Pretzels, weapons, a kitschy tea set: the non-hierarchical treatment of content and the simultaneity of stories, as we encounter them on social media, both unsettle and fascinate her. »I can’t believe I can watch a nighttime skincare routine, learn about thirteenth-century England, and watch someone abroad be killed on camera within the same hour. I try to capture that feeling of not fully knowing where you are in space and time in my work. This might not be melancholy, maybe disorientation. My inner world is much less poetic than melancholy.«

Materials, forms, and structures surrender themselves in the paintings of this artist. Wood has painted over the original motif once, twice, three times—in some instances creating layered surfaces where it no longer matters what counts as background and what has already pushed into the foreground. The work Wood presents in her Schinkel Pavillon show circles around the question of how images come together and how they fall apart; around fantasy and solace; around the timeless hope that something must exist behind things, ready to reveal itself in the act of looking—and around the fear that there may be nothing there at all, that it is not we who expose the images, but the images that suddenly expose us.

›Issy Wood: Magic Bullet‹, Schinkel Pavillon, 11 SEP 2025—25 JAN 2026