This article first appeared in the Berlin Art Week 2025 special issue of Freitag.

Behind Leopoldplatz in Berlin stands an old building. In Regina Scheer’s novel ›Gott wohnt im Wedding‹ it tells its own story—of what happens in its courtyard and between its walls. While the tenement block becomes the narrator, the tenants whose fates it recalls are merely extras in its century-spanning history. Something similar can be said of the most monumental work in the exhibition ›Herbst‹. With this show, Haus am Lützowplatz (HaL) opens Berlin Art Week with the largest institutional solo project to date by painter Ruprecht von Kaufmann in the city he now calls home.

On the almost three-metre-high and five-metre-wide oil painting ›Herbstabend‹ (2024), an urban courtyard scene unfolds in great detail. At dusk, a figure marked by life’s hardships bends over a dustbin, a bag of scavenged goods at their side. Unimpressed, two women lean out of the windows above with cigarettes, while nearby another woman in a leather jacket props herself against the wall; her hunched posture and the discarded wine bottle hint at looming trouble. Five bald-headed figures in bomber jackets march across the yard below, accompanied by an attack dog every bit as muscular as they are.

Born in Munich in 1974, von Kaufmann studied at the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, near Los Angeles—the epicentre of cinematic storytelling. Its influence is still felt in his figurative painting, in the almost filmic sequences with which he narrates anonymous urban life.

The scene of ›Herbstabend‹ appears as though glimpsed from a window in the house opposite. Yet this perspective begins to crack once one withdraws from the physical pull of the giant canvas. Towering overhead, it unsettles the viewer’s footing and places them somewhere in between—somewhere, too, where the other paintings by von Kaufmann find their form: in a threshold space.

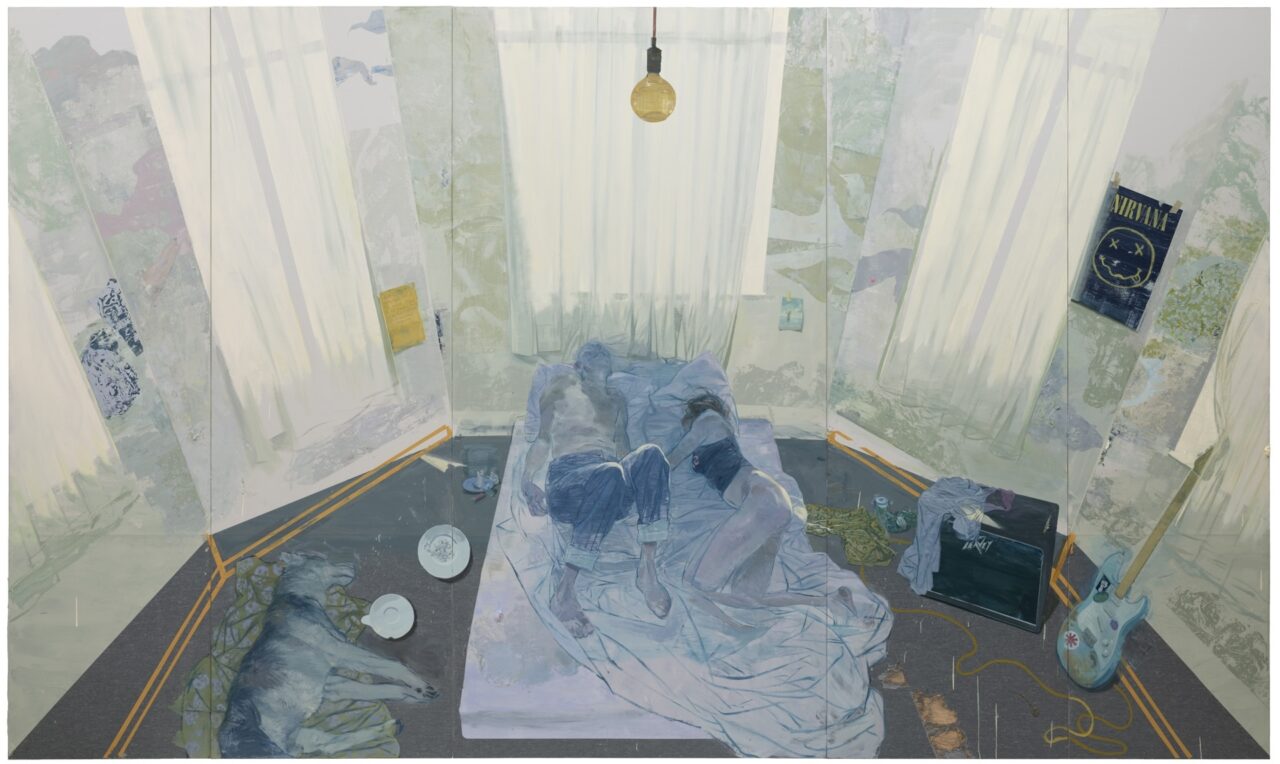

From seemingly everyday motifs, von Kaufmann develops studies of instability. Conceived especially for this exhibition, his oil paintings—at times incorporating collage—translate the painterly play with perspective into the exhibition space itself. In one bay window at HaL, for instance, hangs a work that mirrors the very architecture of the alcove while simultaneously producing dissonance between the actual and the painted.

This deliberate disorientation—placing viewers in perspectives that remain unresolved—echoes the fleeting moments of city life von Kaufmann captures. His often sombre worlds, populated by figures teetering between melancholy and agitation, spring from the present: one painting shows tattooed bodies in tribal-flower style, dancing. Repeating patterns on clothing, skin or wallpaper are applied with stencils, which at times also make their way onto the linoleum support itself. As the artist explains, this material allows »a more aggressive style of painting«.

At the same time, von Kaufmann draws stylistic and narrative parallels to the political and social realities of the Weimar Republic. References to Otto Dix’s depictions of a fragile society in the interwar years can be found in titles, tones or depictions of urban confusion—inhabitants seldom alone, yet often lonely.

What may seem like fleeting scenes often reveal themselves, on closer inspection, as situations of danger, glimpses of human abysses, subtle foreshadowings of crisis. The painting ›S-Bahn‹ (2025) suggests as much: fleeting flashes of light reflect in the windows of a tram rattling through the night. Just within the frame, a man sits with his back to the scene, his shoulders lost in an oversized jacket, bony fingers clutching a red handbag. Beside him, a woman props her elbow against the narrow window ledge. Their vacant stares drift outside the frame to the left, as if looking back at lives already behind them. More engaged with the past than with the four men sitting opposite, they miss the taut arm of a red-faced youth stretched mockingly towards a limping guitarist. The gesture hardly seems playful.

Anyone still in doubt, stepping closer, will notice that on the youth’s polo shirt, in place of a logo, a crowned figure performs the Nazi salute. It is in the shift between overview and detail that the complexity of von Kaufmann’s compositions emerges. By breaking with a single central perspective, the viewer is compelled to look again and again, seeking orientation in the unstable ground of these paintings.

A visit to the artist’s studio shows that this breaking open of pictorial space does not end at the edge of the canvas. On entering at ground level, a second door suddenly opens onto nothing: the floor of the ground storey, in which one thought oneself still standing, has been removed. The airy studio now extends from basement to the ceiling of the first floor. A brilliant intervention, perhaps, protecting the artist himself from the pitfalls of an »ideal viewing position«, which, as von Kaufmann remarks of his works, ought to be excluded altogether. »Pictures move when they set the viewer in motion,« he says. The staged moment of disorientation forces a renewed perception of one’s surroundings—and makes the fractures and crises of the everyday visible where they would otherwise remain hidden in passing.

›Ruprecht von Kaufmann: Herbst‹, Haus am Lützowplatz, 11 SEP 2025—4 JAN 2026

English translation by Amy Patton on behalf of Berlin Art Week