A smiling young man with a short afro sits comfortably on a black plastic chair, leaning casually against a nearby metal table support. He is wearing black trousers, topped by a rose-patterned shirt unbuttoned almost to his navel. In his right hand he cradles an old-fashioned rotary telephone; his left holds the receiver—connected by the once-ubiquitous spiral telephone cord—to his ear. The photograph is a kind of time machine, transporting us to a bygone era when a young person might lug the family’s home phone into their room, then sprawl out on the floor by the door for marathon chats with friends because the line would reach no further.

»If you play with me, I will play with you«, sang Prince Nico Mbarga in his 1970s hit ›Simplicity‹. Performed with his band Rocafil Jazz, the anthem helped catapult the singer to fame across West Africa. The line also perfectly embodies the spirit of Samuel Fosso’s first photography series, ›70’s Lifestyle‹, taken between 1975 and 1978. Playful images find Fosso immersing himself in the flamboyant spirit of the decade, experimenting with bold poses and costumes. The characters he assumes oscillate between confidence and introspection; they experiment, try different identities on for size. In that sense, they also recall the groundbreaking studio photographs of the 1960s by Seydou Keïta and Malik Sidibé, whose works such as ›Un Ye-Ye en position‹ (1963) and ›Avec Mon Sac, Bagues et Bracelets‹ (1968) documented precisely the same exuberance of a young generation forging new postcolonial identities. It is a foundational series and one that will surely have its place in the exhibition ›Samuel Fosso. Black Pope. Werke 1975—2017‹ at Kindl—Centre for Contemporary Art, a comprehensive survey of Fosso’s work over four decades.

Samuel Fosso, born in 1962 in Cameroon and currently based in Bangui, capital of the Central African Republic, and Paris, is one of the world’s most celebrated contemporary photographers. Fosso lived with his grandfather in Biafra, Nigeria, until 1975, when he fled to the Central African Republic to escape civil war at the age of 13. As a teenager in Bangui, he opened his first studio, Studio Photo Gentil, where he made creative use of film frames left over from a shoot to create self-portraits. His self-portraits, featuring oversized sunglasses, flared trousers, and high heels—reminiscent of the platform shoes seen on Prince Nico Mbarga’s album covers—vividly capture the Afro-American fashion trends of the era. Yet Fosso’s ›70’s Lifestyle‹ series remained largely unnoticed for many years. It wasn’t until 1994, when he was invited to participate in the inaugural Bamako Biennale, that his work was publicly exhibited and also earned him the top prize at African Photography Encounters.

It is through this physical embodiment and visual narrative that Fosso transforms a deeply personal ordeal into a broader commentary on power and oppression—interwoven with the story of his own act of self-empowerment, another key feature of the work.

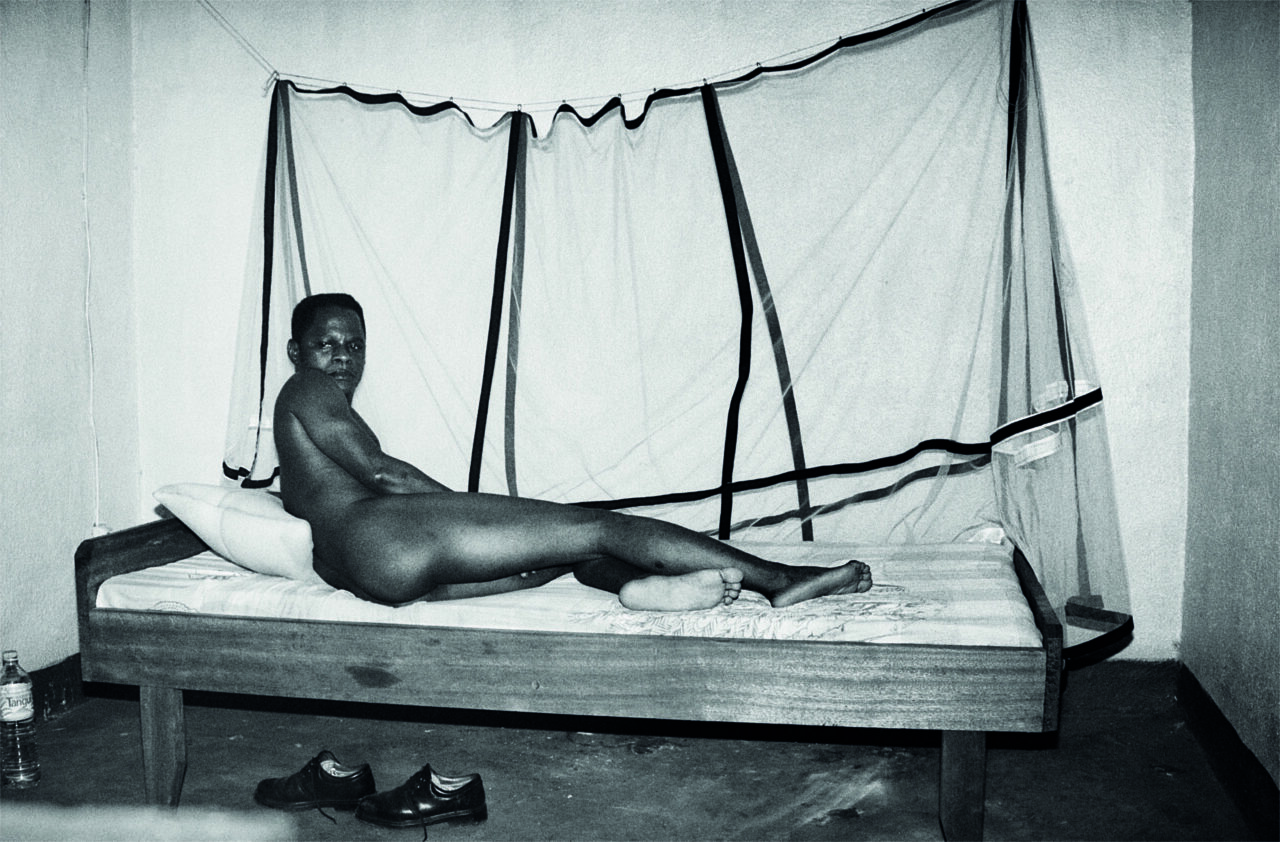

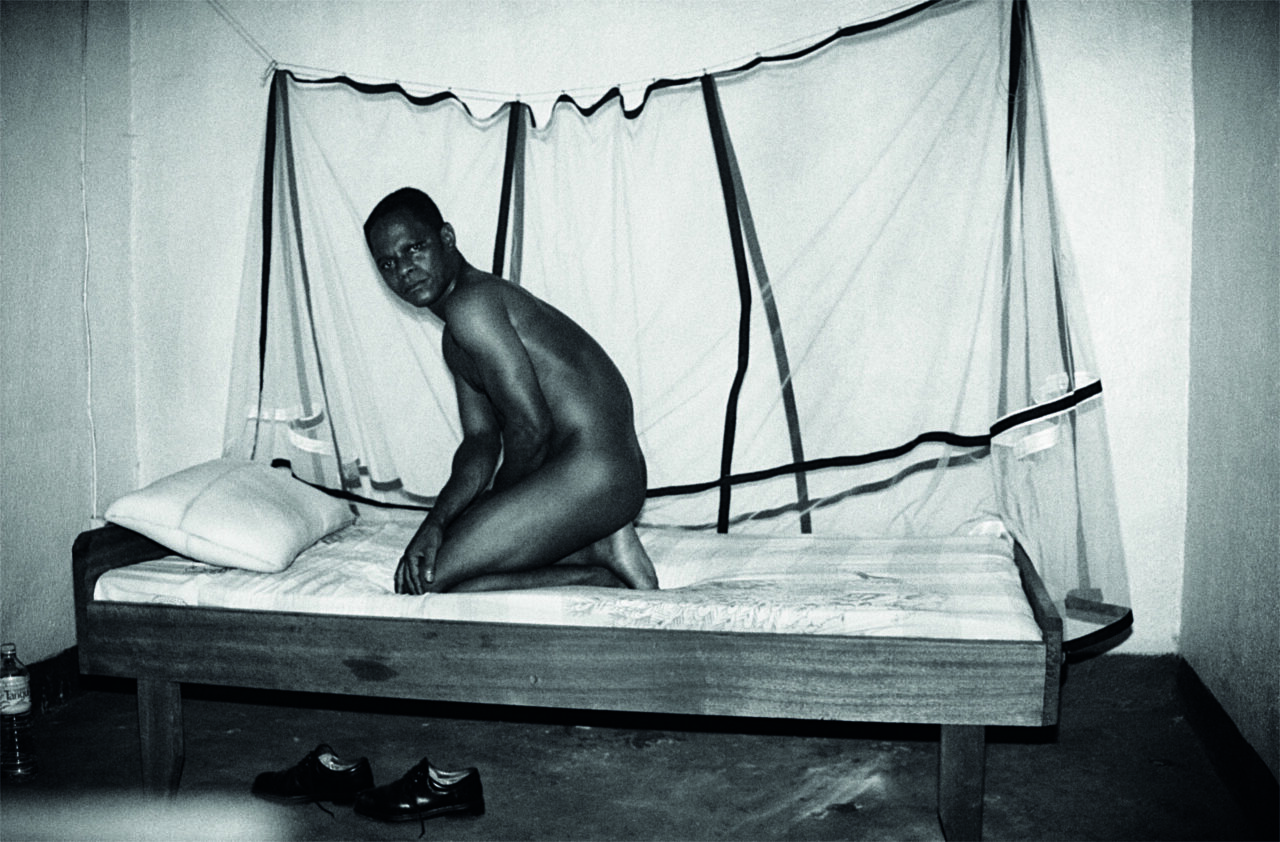

»When I work, it’s always a performance that I choose to undertake. It’s not a subject or an object; it’s one more human being. I link my body to this figure, because I want to translate its history«, Fosso says of his photographs from the year 2000, ›Mémoire d’un ami‹. The series deals with the murder of a friend by members of an armed Central African militia while Fosso was hiding in the same house. The small, horizontal black-and-white photographs show Fosso lying on a narrow bed, black patent shoes on the floor by his side, with a mosquito net hanging behind him. Posing in the austerely furnished room, he presents himself in a vulnerable state—crouched with his hand covering his genitals, half propped up, his back to the viewer, or standing with clenched fists at the door. Although only Fosso is pictured, the sense of another’s presence remains palpable. Fosso draws the viewer in, sometimes meeting their gaze directly, sometimes turning away, but always aware that he is being watched. The viewer is made a witness to his loneliness and grief. It is through this physical embodiment and visual narrative that Fosso transforms a deeply personal ordeal into a broader commentary on power and oppression—interwoven with the story of his own act of self-empowerment, another key feature of the work.

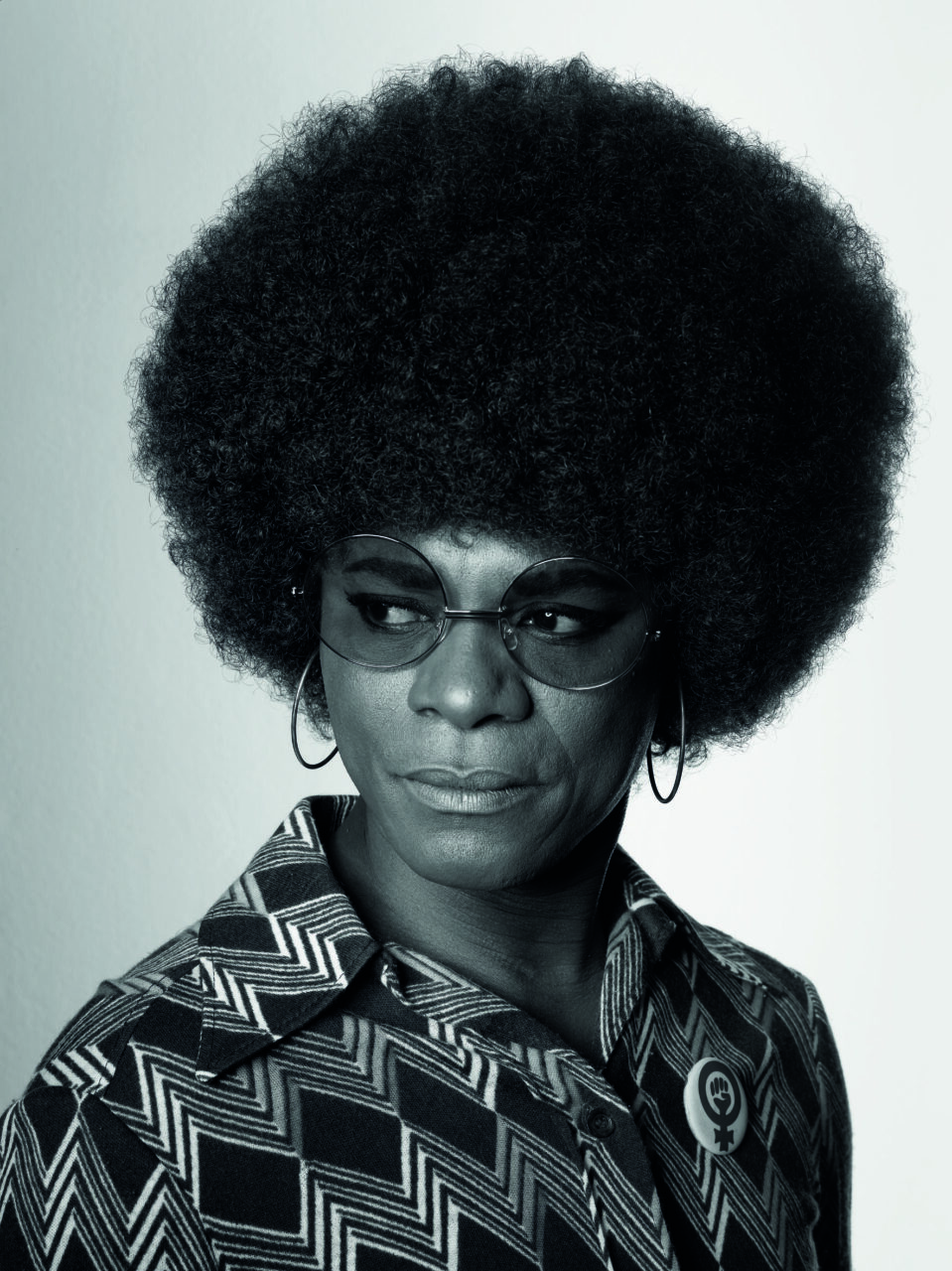

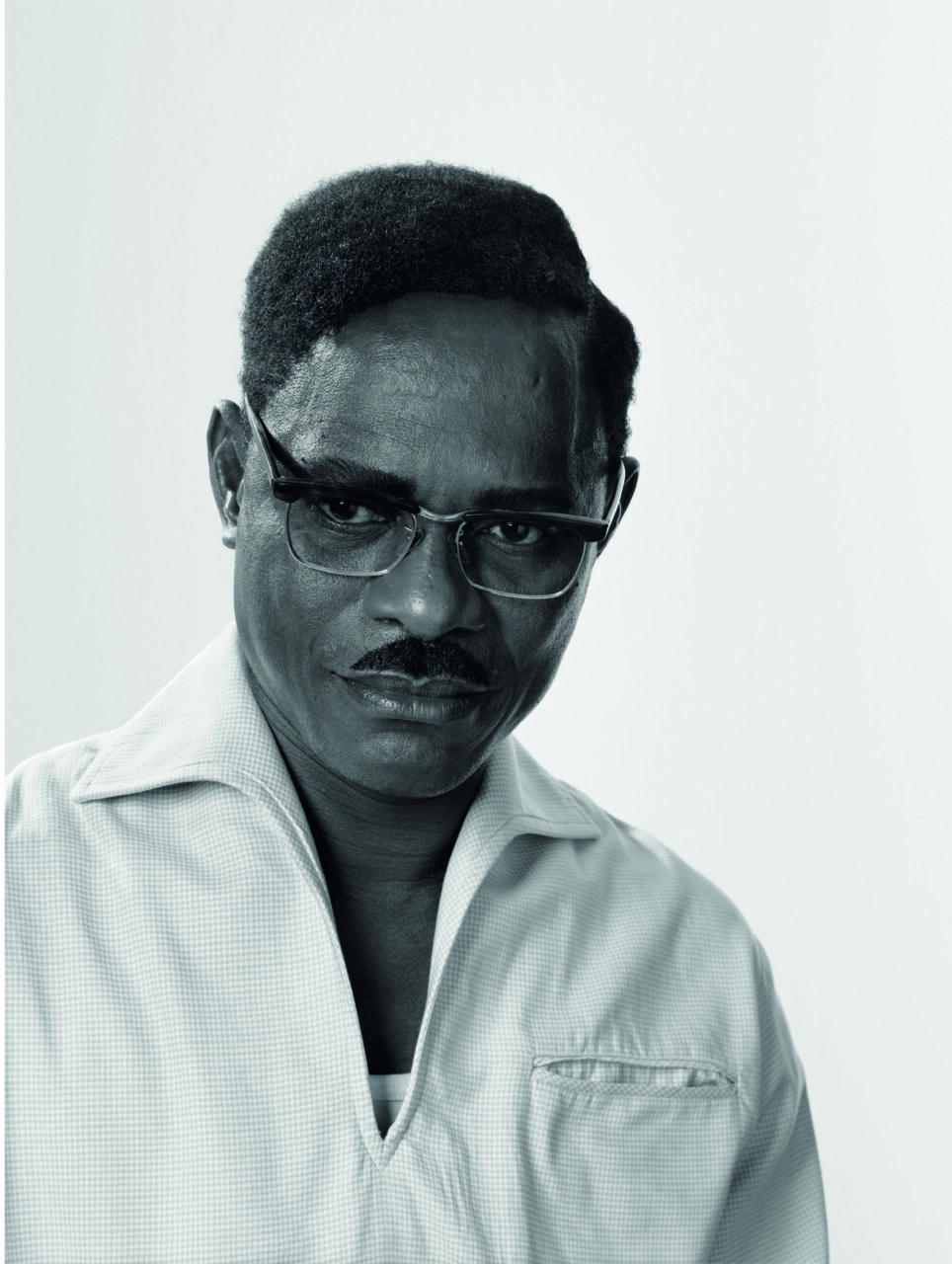

Fosso’s series ›Tati‹ (1997), ›African Spirits‹ (2008), and ›Black Pope‹ (2017) vividly capture how narratives of power and oppression intertwine with questions of memory and collective history. The exhibition at Kindl—Centre for Contemporary Art places ›La Bourgoise‹, a photograph from ›Tati‹, prominently at the entrance. The image shows Fosso posing against a red backdrop in a form-fitting sequined gown, stole, shoulder-length wig, and gold hoop earrings. Kathrin Becker, the exhibition’s curator and artistic director of Kindl—Centre for Contemporary Art, emphasises how it is precisely Fosso’s exploration of identities, media imagery, and social codes—including class and gender—that makes his work such a good fit for Berlin. ›Tati‹ marks a turning point in Fosso’s approach, a shift from traditional studio photography to a more elaborate set akin to the type used in film production. This evolution continues in ›African Spirits‹, where Fosso takes on the roles of prominent African and Afro-American resistance figures and pan-African liberation icons. Some, such as Martin Luther King, Angela Davis, and Malcolm X, are well-known even in Western, Eurocentric historiography. But Fosso also honours less prominent figures whose stories are often excluded from such accounts—probably because they cannot be told without also exposing colonial atrocities, resource exploitation, and the complex power structures created by Western colonisers.

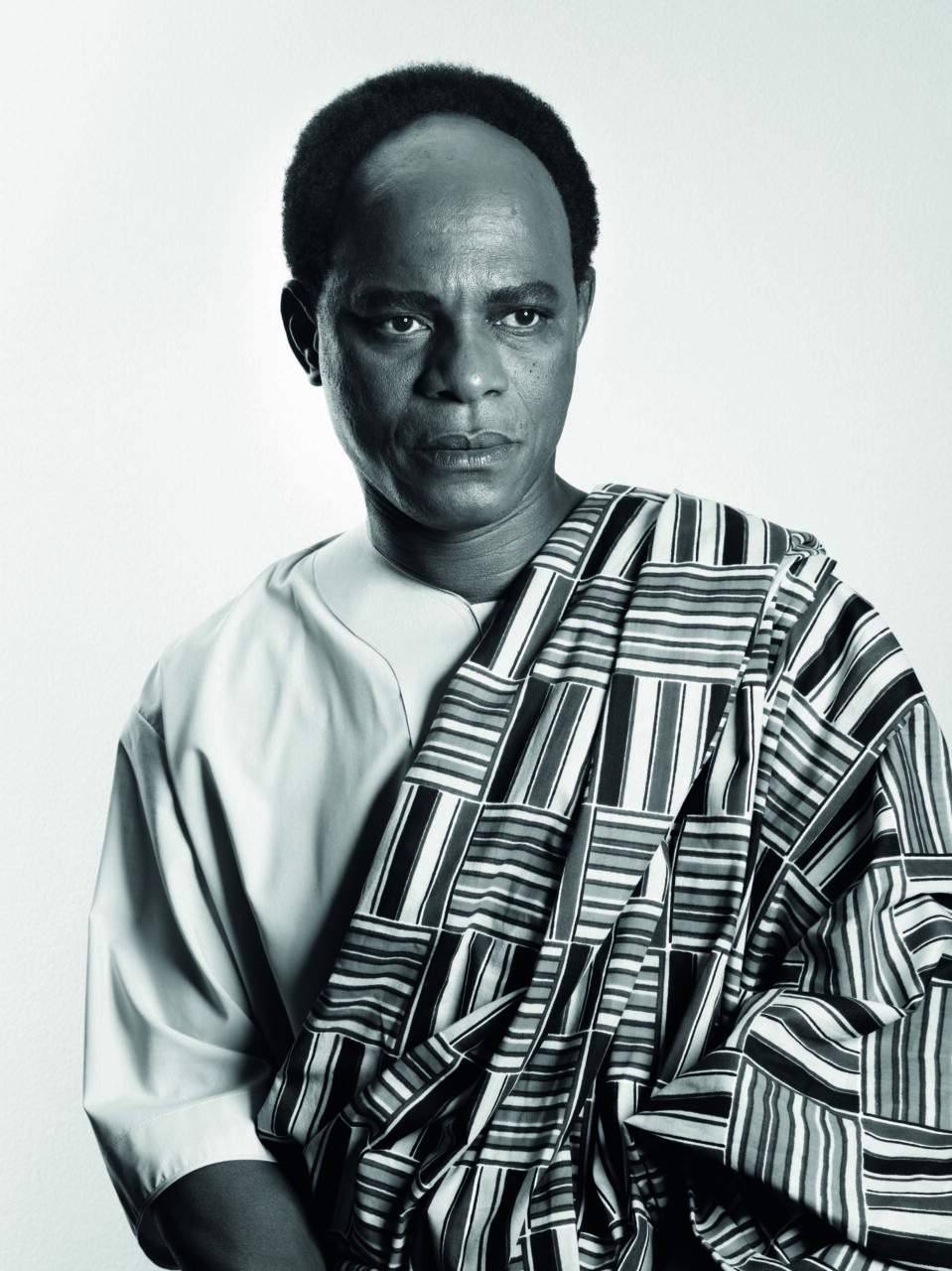

Consider, for example, Patrice Émery Lumumba, who became the first prime minister of the independent Congo in 1960 and championed the country’s liberation from Belgian colonial rule through peaceful means. His assassination occurred in the presence of Belgian officers and officials. Then there is Kwame Nkrumah, the inaugural president of Ghana who emerged as a prominent leader in the Pan-African movement. His tenure ended abruptly in 1966 when a military coup, allegedly supported by the US government’s CIA, overthrew him.

Fosso not only plays his role models, he becomes the person in question.

»Black cultural movements always have to deal with this question of memory because it is only raw material, the only stock that they can return to«, writes scholar Aïcha Mehrez, who explores the legacy of the transatlantic slave trade in contemporary art museums. And that is exactly what Samuel Fosso does: he mines this material and not only plays his role models, he becomes the person in question. He imagines himself as Martin Luther King, as Angela Davis, as Kwame Nkrumah, immersing himself in their struggles, fears, and visions. By telling his own story in the form of others, Fosso mixes the dynamics of individual and collective identity, memory and history, truth and fiction.

›Black Pope‹ takes Fosso one step further: portraying himself as the Black leader of the Catholic Church. It is an image that explores not only the complexities of a possible future, but also, by extension, the problematic colonial past. The Catholic Church has never had a Pope of colour, but on the contrary has been deeply implicated in global colonial history, often intertwining the Christian message with imperialist and racist ideologies. There are now almost as many Catholics in Africa as in Europe, notes Nigerian curator Azu Nwagbogu in his commentary on Fosso’s series.

Just how complex the economic and political landscape of many African countries is becomes strikingly clear in ›Emperor of Africa‹ (2013). In this series, Fosso transforms himself into Chinese ruler Mao Tse-tung—posing in front of a cornfield in an Asian bamboo hat, under a Chinese flag with an African silhouette instead of yellow stars, or wearing a soldier’s helmet in historically styled black-and-white images. Here he is shown not as a liberator, but as the architect and emblem of a modern imperial power extending its reach across the continent. Once again, Fosso masterfully intertwines questions of responsibility, power, and ambiguity to create his own dynamic representation.

Much of Samuel Fosso’s work evokes the extent to which the Black imaginary remains deeply influenced by colonial histories, racism, and stereotypes. His practice not only confronts these influences, but also exposes the significant gaps in how Black people are represented across various aspects of life. Fosso’s personal and political art is a call to Black people and people of colour to embrace their multifaceted identities and embody their complexities. As the artist himself says: »Each person has both so many indefinable particularities and universal aspects, which we all recognise in ourselves.« It is also precisely these aspects that Fosso’s work invites us to explore.