Carolin Schmidt (CS): The title of your nGbK exhibition is ›Orangery of Care‹. Can you give me an idea of what this orangery will look like? What sets it apart from other orangeries?

Lina Brion (LB): Botanical gardens, orangeries, and greenhouses were built to exhibit plants, not only for educational and research purposes, but also as symbols of prestige. These plants continue to shape our visual world today. We often think of tropical plants as exotic, ›distant worlds‹ in which visitors to a botanical garden can immerse themselves. In contrast, Para’s ›Orangery of Care‹ focuses on plants that have already been domesticated—it looks at the homes, offices, and other habitats they occupied before. That might mean talking about the history of the DIY store where they were sold, the industrial greenhouse in Holland where they were grown. It’s not exotic plants we’re looking at, but the spaces brought to life through practices of care.

CS: How would you describe Para’s approach in general? What’s your take on the topic of care?

LB: We think about the present in terms of something that will eventually be the past of a later future, which means we’re basically operating in an ›it will have been‹ mode. It’s from that speculative standpoint that we explore various phenomena of globalisation. This particular project started with the notion of a room full of discarded houseplants that nobody cares for anymore; the curatorial concept came out of that idea. Then we decided to explore the historical dimension by looking at greenhouses, botanical gardens, and orangeries. The overlap or intersection of botanical gardens and their colonial history, but also the whole topos of care, is really embodied by the potted plants we live with every day. As plants, they still have something of nature about them, but they’re actually the epitome of culture.

Amelie Neumann (AN): For me, it’s mainly about social practices and the questions they raise: How do we behave towards each other? At what point does something become in need of care? How are origins overwritten? Why is it so much easier to care for plants than for our fellow human beings?

»Being a caretaker of artistic work is really key as far as I’m concerned.«—Amelie Neumann

CS: What role does care play in your curatorial practice in general?

AN: Being a caretaker of artistic work is really key as far as I’m concerned. It means choosing artistic positions in a way that creates a space of experience, one that is based on a system of mutual support and leads to greater visibility—also among the artists themselves.

LB: Exactly. Working closely with the artists is really important to us in general. I want to build a real relationship with them wherever possible, so they don’t feel like they’re just being picked out and put on display, the way plants were collected and put on display in the orangery.

CS: Is that possible with every artist you work with?

LB: Of course, there are cases where we just deal with the agency that handles the distribution, like with some filmmakers. But then there are artists with whom we’ve had long discussions and worked closely to develop something together. Bethan Hughes, for example, is doing a commission for the exhibition. She has a long history of working with natural rubber, exploring its historical and economic dimensions. But for this project she’s focusing on her own rubber tree, which died when her first child was born. The piece is called ›Limits of Care‹.

CS: How important would you say capacity is when it comes to thinking about care?

LB: We’ve got a number of works in the show that look at the finite nature of caring, reproducing, and regenerating activities, and what it means to be responsible for other living beings. There are also parallels in nature, which itself is by no means an infinite resource. There’s a work by the artist Sophie Utikal, for example, which explores her pregnancy, her relationship with her embryo, and the sense of alienation from her own body. Works like these force us to reflect on our own practices—we notice that we’re also constantly pushing the limits of our capacity to care for one another.

»For us, it’s very much about keeping the plants alive, and that means changing them or allowing change to happen.«—Lina Brion

CS: Care is a prominent topic in contemporary art at the moment.

LB: Right. At the same time, care is often only labelled as a positive thing, without acknowledging its complexity. The flap text of Maria Puig de la Bellacasa’s book ›Matters of Care‹ sums it up really well I think when it says: »But what is care? A moral obligation? A burden? A joy?« We want to explore care as an ambivalent issue. What role can it play in production structures? Which processes are good and which should we just do away with? How can we ensure that our work is sustainable? That’s why we’re including a Para-activation in the exhibition.

CS: What will it look like in practice?

AN: We’ll have a plant collection point where people can drop off their unwanted houseplants. We’ll look after them, take care of them, and try to find new partners for them. We’re curious to see how this exchange works and what social structures are needed for people to part with something and start something new.

LB: Another artist involved in Para, Vanessa Amoah Opoku, kept questioning the way botanical gardens are just like museums, that they’re all about keeping the plants or the exhibits in their original form and preserving them—they’re spaces of control. For us, it’s very much about keeping the plants alive, and that means changing them or allowing change to happen. Plant propagation is part of that.

CS: In what way?

AN: We’re growing cuttings and digitising mother plants to give them a second life. So it’s not just about conservation, it’s about productive use.

CS: What does this digital, second life for plants involve?

AN: We’re documenting the history of the plants. Very early on in the project, we collected plants from Hamburg, Berlin, and Leipzig and documented their respective histories. For example, some of the plants we now have here in the nGbK office originally came from a former open-plan office.

CS: How did that come about?

LB: There was a company that went completely remote and dramatically downsized its office, which meant there was nowhere to put the plants that had been there for 20 years.

AN: Which raises a number of questions: What do you get rid of first? What’s the last thing you get rid of? What happens to things that no one wants? Do people even know what these plants are? Where do these plants come from, apart from the DIY store? Visitors can view these histories and see the identities of the plants in the digital space.

»Reproductive work or care is not something that you can just easily set aside and quit. Not caring is not an option.«—Lina Brion

CS: Care as a subject and political issue was first taken up by the Black women’s movement in the USA in the 1960s. How can decolonial, feminist, resistance-oriented perspectives shape our understanding of care today?

LB: Rather than working with a single, fixed concept of care, the exhibition raises questions about what caring, life-sustaining practices might encompass. What does it mean to understand care as responsibility? To what extent is it necessary to confront historical violence? What constitutes good living conditions? These are all political questions raised primarily by activists, many of whom are marginalised. My view of the concept of care has been largely influenced by Marxist feminism, one of the proponents of which was the philosopher and activist Silvia Federici: The discussion around ›Wages for Housework‹ highlighted the fact that so-called housework is whatever produces the ability to live, which is of course also work. One wonders what would happen if all carers went on strike. After all, if those who stay at home so that the other person can go to work stopped working, the other person would no longer be able to go to work. At the same time, reproductive work or care is not something that you can just easily set aside and quit. Not caring is not an option.

AN: The resistance aspect of the exhibition comes through most when we talk about how we experience temporality in relation to care. What’s the speed of our present moment? We need a new sense of time that doesn’t just revolve around consumption. There’s also an intervention and lecture performance by the Berlin-based artist and curator Anguezomo Mba Bikoro as part of the show’s accompanying programme. Drawing on their own engagement with plants, they’re looking at health care and the relationship between care and ecology through a decolonial, Black feminist lens.

CS: Do any of the works in the show address those aspects in particular?

AN: The artist Dunja Krcek bases her paintings on the movement of plants. We often talk about plants as if they just sit there and vegetate, but if we really take the time to observe, we can see how they move. For that, you need deceleration. This process of slowing down also has a political dimension. Samir Laghouati-Rashwan’s installation focuses explicitly on the colonial history of botany. Many plant names given by white colonisers and scientists were arbitrary and ignored the knowledge of the people who had lived and interacted with these plants for centuries. The names of plants often contain important information, such as whether a plant is medicinal and what illnesses it might help. The plant used to make quinine, for example, which is found in tonic water, is actually a medicinal plant.

LB: A video by Rob Crosse shows a group of scientists in a forest carrying out dendrochronology, the process of determining the age of a tree by studying its rings. The rings also reveal the tree’s health history, information that can be used to determine what conditions the tree needs to survive in the long term. At the same time, the video looks at how plants communicate and support each other, their networks of mutual support. Edited in with this are interviews with people from a queer, intergenerational housing project in Berlin. The residents share their thoughts on growing old and the support systems they have in place.

»Many people are completely unaware of the plants around them and their history.«—Amelie Neumann

CS: When looted art from colonial contexts is displayed in museums, the claims of ownership and abuse of power are obvious. But with plants, it’s more about subtle colonial attitudes that somehow linger on, mostly unconsciously. Has this knowledge changed the way you treat or think about your own plants? Is a decolonisation of our living rooms in order?

LB: I take my plants a bit more seriously now.

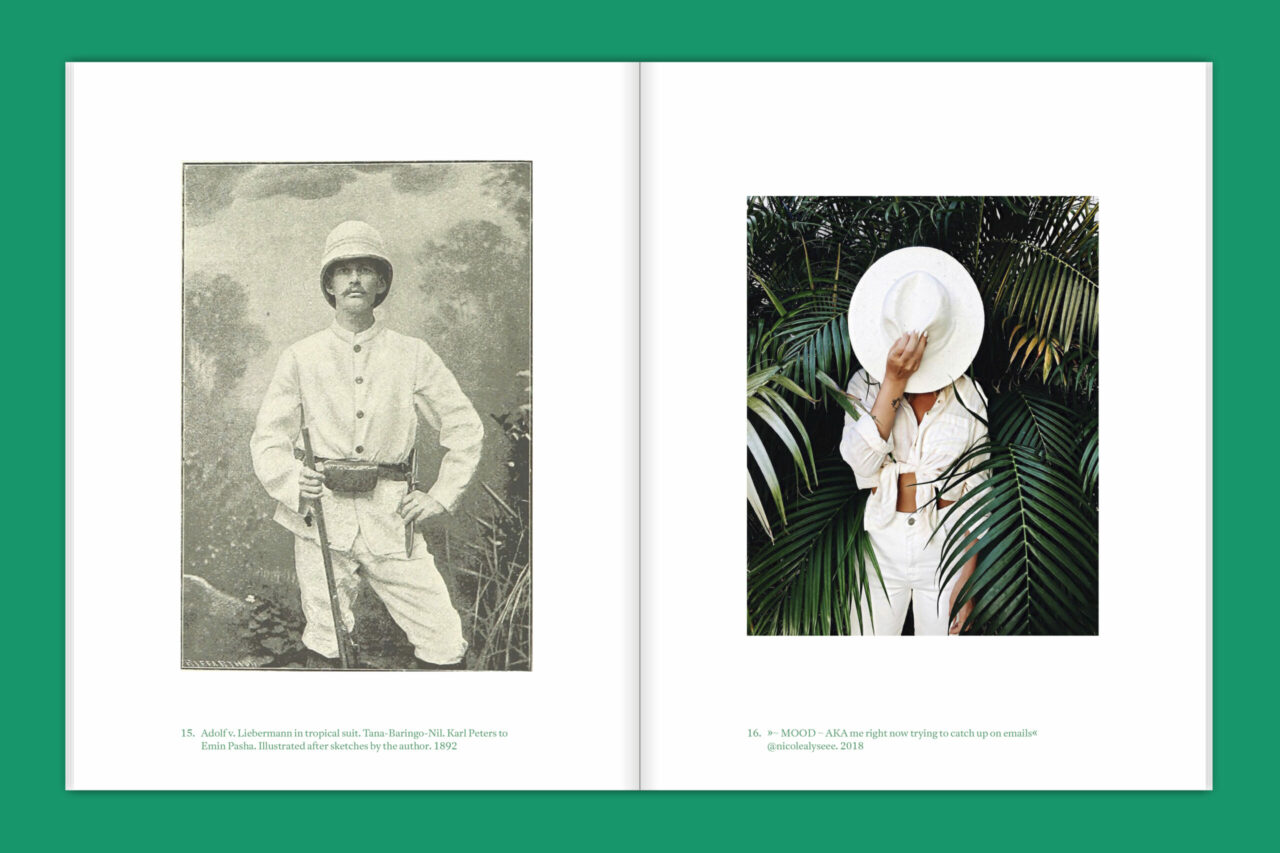

AN: It’s changed the way I view an urban context. I recently walked through one of the older neighbourhoods in Frankfurt am Main and noticed whole streets lined with huge palm trees and colourful magnolias. At first I thought, sure, this makes sense for a city like Frankfurt, where people from all over the world live and bring their own pieces of home with them—then I realised that these plants must have been here for a long time to be as big as they are. Many people are completely unaware of the plants around them and their history. Here I have to think of Julia Löffler’s work ›Plant Hunters‹, where she compares 19th century photographs of people posing with tropical plants in a colonial pose with modern photos of ›plant influencers‹ on Instagram. The similarities are striking and say a lot about this kind of unconscious, lingering mentality.

CS: Was there any particular literature that influenced you while working on the exhibition?

LB: Parallel to the process of conceptualising the exhibition, I read ›Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds‹ by Maria Puig de la Bellacasa. She talks about ›care‹ as all the activities involved in keeping something alive. Another book that was very important for our work was ›The Coloniality of Planting‹ by Shela Sheik and Ros Gray. It raised the question of whether reimagining or changing our relationships with plants might also help us rethink relationships between people.

CS: How do you imagine the future of care? Where in our daily lives do you see an opportunity to think about the way we care for each other differently or organise it in a different way?

AN: There’s an interest in showing that care work is no longer just something that’s tied to families of origin, that there’s a social mechanism of distribution. Anybody can be a provider of care—care for themselves, for others, for the environment. Emphasising this would also show what care work actually means.

LB: To sustain ecosystems, we need regenerative practices. That can be anything from doing household chores to caring for other people and living things. Basically, society should be organised around principles of life support and regeneration.

CS: Any plant you’re particularly fond of?

AN: I’m partial to the mother-in-law’s cushion. It’s such a beautiful, round cactus—it’s untouchable and unchangeable. At the same time, it’s a very well-adapted plant that gets by with little care and little water, a situation we might also find ourselves facing.

LB: The flat I’m in now is the first one I’ve had a few plants in. One in particular is a real source of joy, and it’s smallest of all: a Mallorcan desert cabbage. I got it from Para as a little offshoot of two others. It’s so cheerful looking and I love the way it just slowly grows and sprouts.

CS: It’s been great speaking with you all, thanks for the interview!