Dominikus Müller: During Berlin Art Week you will open ›Display‹ a show by Sara Ouhaddou. The exhibition at ifa-Galerie Berlin is just one leg of the project, the other is on view at the same time at the Museum of African Contemporary Art Al Maaden Marrakech. Why this double approach?

Alya Sebti: Meriem Berrada, the artistic director of the contemporary art institution Al Maaden (MACAAL) with whom I am co-curating the show, and I want to create a complementary experience. Underlying is a question I am interested in for quite a while now: How can we—working from within a German institution—do something relevant and sustainable in another country? We’ve already tried something similar with a recent joint venture project, initiated by KW—Center for Contemporary Art in Berlin and ThinkArt from Casablanca, which turned towards the highly influential School of Casablanca. Around the mid-20th century, the School of Casablanca was formative in establishing contemporary art in a newly independent Morocco. We held an exhibition programme here in Berlin, while, for over three years, in Casablanca a library and an art centre have been created for the local public.

And for the new show?

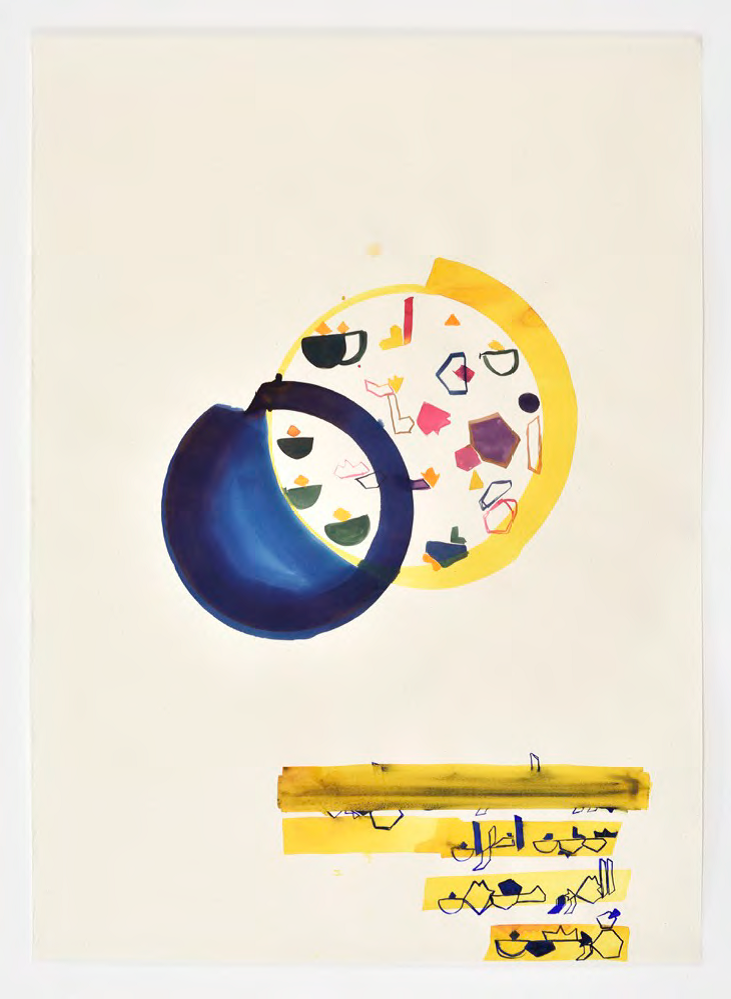

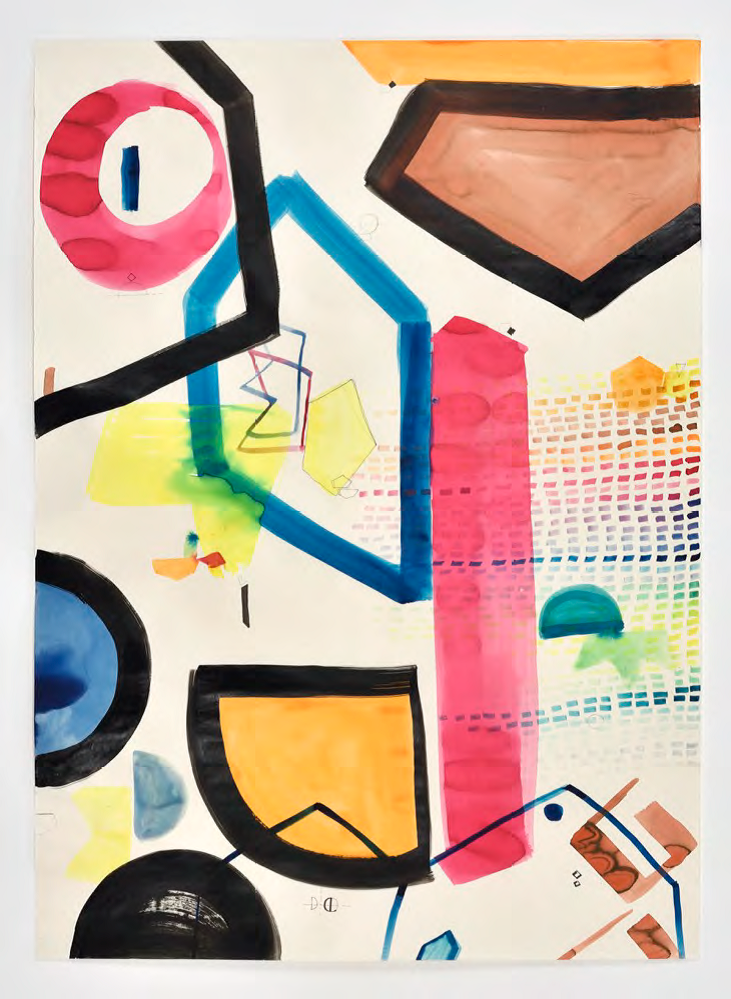

Sara Ouhaddou’s show aims at developing an autonomous way for artisans and artisan communities in Marrakech to follow their own practice. In her practice, she usually questions history through objects—investigating their genealogies, dissecting their functions and extrapolating their forms. Shen then fabricates and refabricates them with the help of experienced craftsmen. Our exhibition now functions as a prelude of sorts to a longer programme that—if everything works out— provides three artisan families from Marrakech with a working model to produce the goods they actually want to do—products outside the usual tourist economy that Marrakech is so dependent on. They come from different backgrounds—we have the Abiada Family who is working in jewellery, Fouzia and Said Yagoub who are producing ceramics, and Amin Hassani doing embroidery.

So the project puts forth an extended idea of collaboration, right?

Exactly, the idea of collaboration and its possible forms are key to the project. There is not only the above-mentioned collaboration by two institutions, but more important, there is also the collaboration between the artist and the artisans. With some of them, Ouhaddou has already been working for around 10 years. Initially, she commissioned them to do work for her—so the more classical, conventional, and, ultimately, hierarchical model of employing artisanal work within a fine arts context. But over the years, their collaboration has been evolving. During the pandemic, then, Ouhaddou initiated an extended form of collaboration and tried to establish new modes of working together. The artisans started to try out completely new stuff, embroidery on caoutchouc for example. Ouhaddou then started to think about a model which could enable them to go on to do stuff like this without needing her as the artist who authorises what they do.

»The question is: How can the spheres of arts and craft meet at eye-level? How is a more fair or ethical way of working between artists and artisans possible?«

—Alya Sebti

How do you plan to achieve this? Normally, when the category of ›the artisanal‹ is referred to within the context of fine arts proper, it is often employed to ›critically‹ question the idea of autonomy—but ultimately, only the side of fine arts is benefitting. The artisanal side, on the other hand, is, once again, being reduced to a certain ›use value‹.

Well, normally, an artist commissions an artisan, pays a certain fee—and that’s it. The artisans are rarely present in the finished work, neither by name nor do they benefit economically form further developments. For the project, Ouhaddou now follows three different models of collaboration: first, the classical one, where the artist commissions a work; second, the same logic inverted—the artisans commission the artist; and third, some middle ground, a joint work on a shared project. What we are going to present in the exhibition will be the products of these ongoing collaborations. Meanwhile, Ouhaddou is creating a mind-map of sorts that makes transparent the thinking behind the project and its processes.

Is the collaboration supposed to go on after the exhibition?

Yes. But in the end, the artisans should also be able to produce and, quite important, sell their work themselves. We want to get them out of the tourist economy. We will create an Etsy platform for them to sell their works directly; we’ll set up Instagram pages for advertising. The real goal of the project is the development of a long-term autonomous business model—dissemination, accessibility, production, all of it.

Some sort of exemplary infrastructure measurement, basically.

Exactly. One, that tackles the relationship between artists and artisans and tries to overcome the hierarchy between arts and craft. The question is: How can both spheres meet at eye-level? How is a more fair or ethical way of working between artists and artisans possible?

You mentioned that you want to take the artisans out of the ›tourist economy‹. How does this economy, this market, affect the actual goods produced as well as their aesthetical and formal quality?

Well, when these artisans from Marrakech produce something, they mostly imagine how a tourist would like it to be. There is a lot of projection involved here, and this blocks off their creativity and drastically narrows down the forms of expression. The tourism circuit thus has a huge impact on the artisans and their traditional ways of making, the motifs shown, the techniques involved, as well as the question of how to further develop those techniques and traditions. For example, the Abiada family produces very classical Moroccan jewellery which you can buy in the Medina in Marrakech. They themselves are very passionate about the Tbourida, also called ›Fantasia‹—a traditional Moroccan horse-riding sport. They visit as many tournaments as possible and now started to create jewellery themed around this sport. Something like this didn’t exist so far. Ultimately, they are not producing what they think the tourists are going to buy, but what they are interested in, something that shows their world. This jewellery, too, will be on view in the show.

That’s a great example of how infrastructural questions can be linked with formal and aesthetical ones! Usually, I feel, infrastructural approaches tend to neglect or overlook the aesthetical and formal side of things.

But, you know, in the end, it’s the look of their goods, the ›beauty‹ of things, if you will, that helps these families to sell something and make a living. So formal questions are extremely important! You are right, though, it feels that putting an eye on beauty and the production of something that is essentially beautiful has—at least for the last years and especially in a city like Berlin—been seen as something slightly cheesy.

During the last years, lots of energy went into tackling important institutional biases and trying to change things on a systemic and infrastructural level. Do you think it’s time to re-integrate questions of form again, but filtered through all these achievements and shifts?

That’s exactly what I’ve been trying to do at ifa-Galerie Berlin for a while now. The last shows there tried to reclaim what we may call a certain ›beauty‹—beauty as an essential part of experience. Just because something is beautiful or formally interesting doesn’t mean it’s cheesy or even non-political. As important as it is to look at the infrastructural level and try to change things there, it may be time to claim back what has been lost or overlooked in the course. It really does feel to me that these questions are to come back under different circumstances.

»If you want to tackle the colonial structures of the everyday, you need a structure that is not only ongoing and sustainable, but also accessible.«

—Alya Sebti

Immediately after you started at ifa-Galerie Berlin, you established an overarching programme structure, called ›Untie to Tie‹. What’s that all about?

Well, ›Untie to Tie‹ is supposed to investigate the colonial structure of the everyday. Everything I do at ifa-Galerie Berlin is happening under this umbrella. It is different now, but back in 2016, I feel, these questions were rather new, especially in Berlin. Of course, there already was a space like Savvy Contemporary, which was dedicated to questions of decoloniality. Being able to raise these topics within a state-funded art institution like ifa-Galerie Berlin felt like a big step up. And I am extremely happy to see how these questions have spread and are now tackled everywhere—not only a critique of colonial structures, but also questions of diversity, migration, ecology, all of that.

How then does ›Untie to Tie‹ relate to the infrastructure of ifa-Galerie Berlin?

With the programme, I wanted to create a rupture withing the institution itself. ifa supplies the framework and gives us the freedom to do what we do, for which I am very grateful. So, ifa basically hosts ›Untie to Tie‹, providing an umbrella for another umbrella. And this enables a form of programming that breaks away from the classical succession of one exhibition after another. Instead, ›Untie to Tie‹ is much more oriented towards research—exhibitions, public programmes, different encounters, performances, sound elements, and, quite important, a digital platform. Because connecting places, people, and ideas as well as sharing knowledge is central to the whole approach. If you want to tackle the colonial structures of the everyday, you need a structure that is not only ongoing and sustainable, but also accessible.

Speaking of accessibility—I’ve noticed that sound and sound-based art practices feature quite prominently in your programme. And it seems to be similar at other institutions engaged with postcolonial discourse and practices, just look at Haus der Kulturen der Welt here in Berlin, for example. Is there a special connection between media and content, so to say?

Well, the body almost naturally responds to music and in a wholly other way than to visual arts. There is a certain playfulness in sound, and a certain beauty. It speaks to all the senses, it fosters presence. And yet, sound has many layers, many access points. It is at the same time highly discursive and political but cannot be reduced to that. And immersing yourself in sound also comes with a certain moment of loosening up. With all that, it is far more accessible and open than much of contemporary visual arts. And thus, more inclusive. Sound comes—if you want to use these words—with a certain universality.

When you started ›Untie to Tie‹ in 2016, the artistical as well as the political landscape was quite different. What has changed for you during these years?

When I started, I was anxious that the new-found attention for questions around colonial structures, the decolonial and so on might just be the next trend within the arts. Here today, gone tomorrow. But fortunately, it turned out differently. Now these questions are more present than ever. Though by now, I am not so sure anymore, how much further into the structure of an institution or the society this will go. I was more optimistic a few years ago, but since then, there has been a drastic backlash, e. g. in the wake of the whole discussion around documenta fifteen. Generally, everyday racism and xenophobia within society just keep increasing again.

How to go on from here, then?

For me, first and foremost, I think it is vital to make sure that the programme stays on its way. I have to say that I never have been censored so far and that up until now my programme has not been affected. But I do see a growing need to actively work against self-censoring. It is important to keep the room for discourse and discussion open. This is crucial to me—carving out a space that enables critical thinking and dialogue, and work on keeping it open. And this also entails—today more than ever—working on long-term alliances with other institutions, other people, other spaces. Or, to use categories of sound once more: what we need is not a single voice but polyphony—interacting, sometimes contradicting, then complementing each other again.