David Apakidze (*1998) lives and works in Tbilisi, Georgia—a country where the rights of queer people are increasingly under threat. His installation ›The Knight at the Crossroads,‹ presented by Kvost—Kunstverein Ost, tells the heroic journey of a queer migrant who appears as a modern knight. Unlike in the classic myth, in which the hero returns triumphant, this knight remains trapped in constant motion and uprootedness. The work reflects the experiences of many people who are forced to leave their homes in the face of political violence in order to find safety.

In his work, David Apakidze combines artistic expression with political activism, focusing on queer perspectives. He is co-founder of the Fungus Project—one of the first queer art platforms in the Caucasus. As this year’s Kvost scholarship recipient, David Apakidze will receive the Claus Michaletz Prize 2025. The exhibition is part of the Featured section of Berlin Art Week.

Your exhibition is titled ›The Knight at the Crossroads‹. What narrative unfolds within it?

I see the knight as a queer person who is leaving their own country to go somewhere for a better life. Migration is often seen as a weakness, as if you are scared to stay in your country or too lazy to

do something, and that you simply choose a better life. But I don’t think migration is a weakness. Even in mythology, the hero becomes a hero precisely by leaving their birthplace, facing dangers, and overcoming bad powers along the way. For me, a queer person who leaves their own country is a hero, a brave person, because it is really complicated to leave your own place. I can’t imagine how to do that myself.

Migration recurs throughout your practice. Why does this theme hold such significance for you?

In the last two or three years, many queer people from Georgia have left the country to seek asylum in the EU. What used to be a vibrant community now feels empty. At parties, where once there were many, only small groups remain. It creates a deep sense of loneliness, both for those who leave and for those who stay behind. Being without your community, alone in a shelter, waiting for asylum must be very hard. Migration is also about the road you take, so I used objects like road signs and a car door—objects associated with travelling. They look familiar but also strange, like something you know that has changed. For me, that reflects the feeling of leaving home: once you are gone, only the image of it remains, and it begins to lose its meaning. My work is about these places that no longer feel like home.

When you think of Georgia’s queer community, which emotions resonate most strongly with you?

For me, the queer community is about the family you choose. Unfortunately, right now I also feel fear and loneliness. As a child, I always felt lonely, as if I were the only gay person in the world. After I found my queer community, I didn’t feel alone anymore. But recently, loneliness is returning because the government and society are trying to erase what we built. That feeling of erasure and loneliness is painful.

»When I first studied Orthodox art, I felt alienated because I was gay. But later I understood that Orthodoxy and Georgian identity are part of me too.«—David Apakidze

Have you ever contemplated leaving Georgia yourself?

I have long thought about migrating from Georgia, but somehow I feel I cannot go.

Loneliness is a recurring presence in your words. What sustains you when that feeling arises?

Friendship. For me it’s the most important kind of relationship. Friends, family, and making art help. Art transforms painful feelings into forms and concepts. It’s a kind of therapy, a way to sublimate hardship into something beautiful.

Your practice frequently engages with symbols and iconography. What draws you to reimagine familiar imagery, and what do symbols allow you to express?

I studied art history and spent a lot of time studying medieval art. Christian art builds on symbols and iconography. When I first studied Orthodox art, I felt alienated because I was gay. But later I understood that Orthodoxy and Georgian identity are part of me too. That was the beginning of my idea to create a queer iconography of Georgian art. Symbols are not just images—they were created long ago and carry meaning. By reusing them, you become part of something bigger while adding your own identity.

Is there a symbol that has special meaning for you personally?

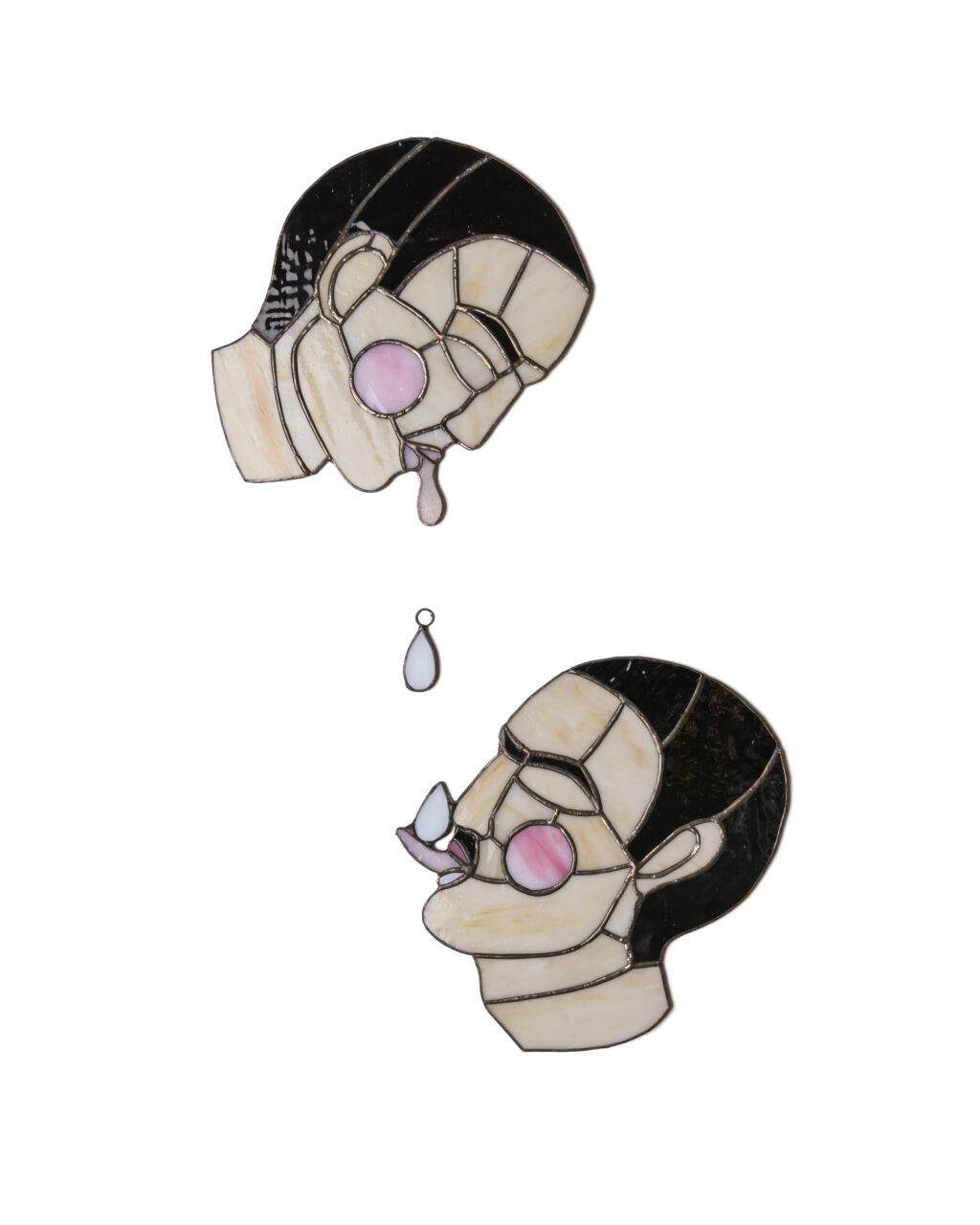

Yes, two: The pink triangle and the green carnation. One of my first stained glass works combined them. For me, together they are symbols of resistance.

You’re part of Berlin Art Week. What does this mean to you?

It means being seen, which is very important. Not only for me as an artist, but also for the Georgian queer community and queer culture. As queer people from Georgia, we are not visible enough right now.

What words of advice or encouragement would you share with young queer artists beginning their journey?

I want to tell them what I wish I had heard when I was younger: you are not alone. Together, we can fight all the craziness happening in this world.

And if you could wish for one thing, what would it be?

May I give the classic beauty pageant answer? World peace! Honestly, my biggest wish right now is for my country to be free and truly independent. Georgia has existed for a very long time, with a beautiful culture and talented people. Unfortunately, it is always caught in political struggles. It is hard to accept that this country could be such a beautiful place to live, but right now, it is not.

Credits for images: Untitled, 2025; Spit, 2025; Snake Eater, 2025 © David Apakidze & Kvost, Berlin