This article first appeared in der Freitag.

Rirkrit Tiravanija is arguably one of the most interesting and approachable figures in the art world—a world that certainly has its share of intriguing personalities. Born in Buenos Aires in 1961 and raised in Thailand, Tiravanija built an international art career that took him to Berlin early on, and where his archive remains today. In fact, it’s here—under the directorship of Jenny Schlenzka, who recently took the helm at Gropius Bau, alongside curators Yasmil Raymond and Christopher Wierling—that Tiravanija’s first major retrospective is opening to the public: a presentation of over 80 works from a career spanning more than 40 years.

As solemn or even pompous as that sounds, Tiravanija’s work is anything but; it is engaging, welcoming and, above all, accessible. Not that Germany was accessible to him at first. He was refused a visa for his first German exhibition at Galerie Max Hetzler in Cologne in 1993, on account of his uncertain US residency status. Undeterred, he realised the work ›untitled 1993 (café deutschland)‹ by faxing the instructions for building a bar where visitors could brew Turkish coffee. It was a clever, warm and painful commentary on the growing racism in post-reunification Germany, which had recently reached a tragic climax with the arson attack in Mölln: in late 1992, right-wing extremists set fire to two houses inhabited by Turkish families—a story that also made headlines in the United States.

But can something like that actually help? Is an act as simple as drinking coffee together any way to respond to such brutality? According to Tiravanija, it is. Every human being needs to eat, and sometimes that shared need is enough of a common denominator. Tiravanija radically challenged traditional expectations of a museum by declaring that things like cooking, eating, making music, or drinking coffee together could be art—and he brought all these activities into the esteemed rooms of various institutions.

But doesn’t the dinner usually come after the art? Is this to say the dinner itself is the art? A casual conversation with the person sitting next to you, the act of toasting a stranger? All this is art? All this is art, insisted both Tiravanija and curator Nicolas Bourriaud, whose writings on ›relational aesthetics‹ provided the theoretical framework for what was then still a new idea. Affective art, you could call it. Art that focuses on shared experiences: coming together, celebrating, chatting. What is typically seen as leisure becomes an intellectually charged activity, transformed into a political, even rebellious act.

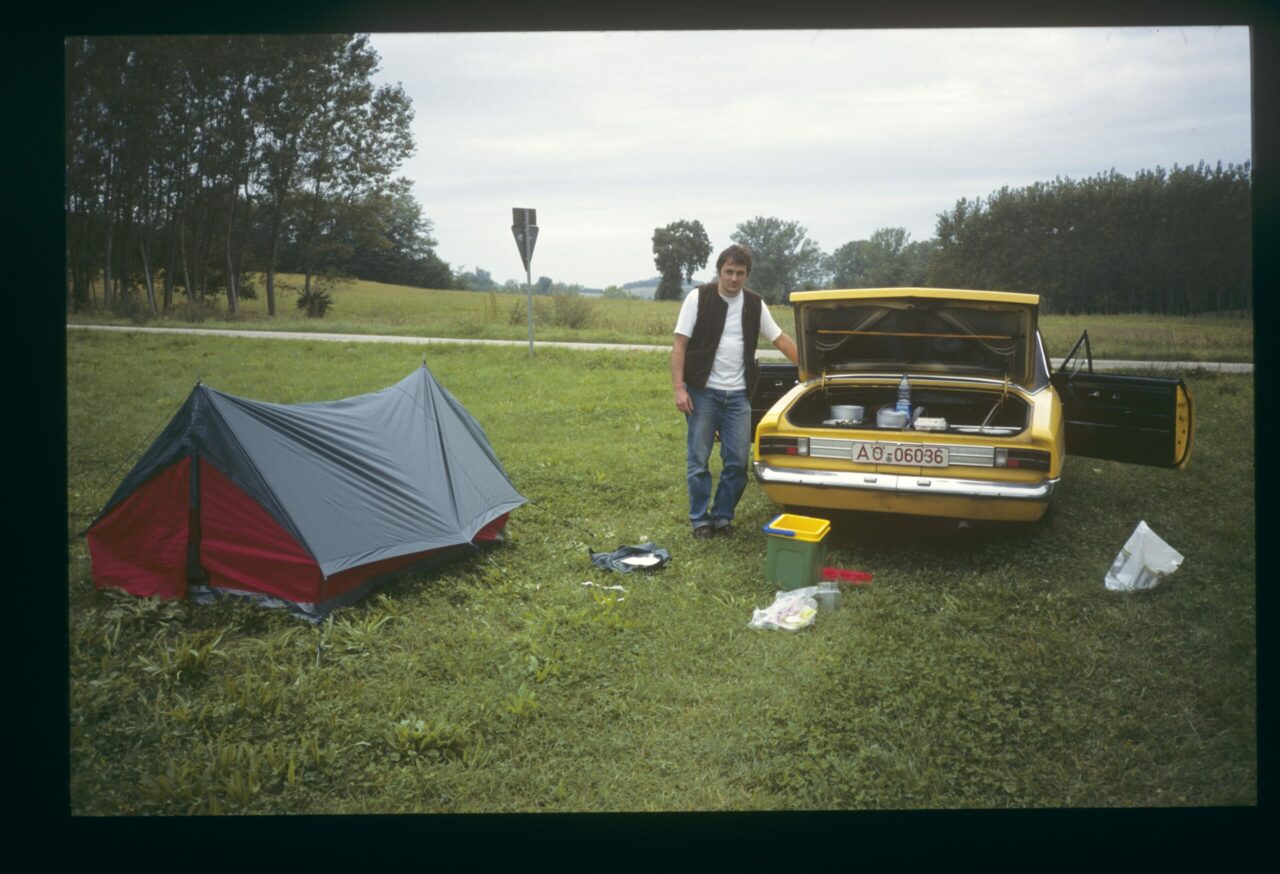

But Tiravanija is more than just »the guy with the Thai curry«. Although he is quoted as saying, »I am not interested in leaving things behind; I am interested in leaving ideas behind,« he has actually produced a number of tangible objects that are now on display at Gropius Bau. Many of these penetrate deep into the German psyche. He has explored the history of so-called guest workers in Germany in the form of Super-8 films, drawings and other works on paper, made films referencing Rainer Werner Fassbinder, whose opening sequence for the 1974 film ›Ali: Fear Eats the Soul‹ inspired the title of this retrospective. Fassbinder, like Tiravanija, looked closely at issues of social oppression and the marginalisation of so-called guest workers. All topics that are very much alive today. Unfortunately.

More than just coffee and cooking

One only has to visit the exhibition to see just how comprehensive Tiravanija’s work is, and how many facets it has beyond cooking, eating and chatting. He ensures that a visit to the exhibition is more than just contemplating a sculpture or painting. On the contrary: the aforementioned coffee bar has been recreated, inviting visitors to slurp a moka together; fifteen ping-pong tables have been set up for play, female cooks from Berlin’s Thai Park prepare his »free food-actions« ›untitled 1991 (tom ka soup)‹ und ›untitled 1993 (flädlesuppe)‹. There’s also a stage in the open atrium of the Gropius building that is constantly being ›activated‹, as the art world likes to say—which is what it’s called in art jargon when something happens on the stage.

What transpires there may seem entertaining or maybe even out of place in a museum, but it raises essential questions about who is welcome in these spaces, who can afford the price of admission, who feels comfortable in it and who doesn’t. After all, this also serves to dictate who participates in the artwork and who does not. Just as Tiravanija casts a skeptical light on this, he also raises the broader issue of what is collected and preserved in a museum like this one, and who gets included in the canon. The fact that he himself belongs and is very much a part of that canon is proved by this retrospective—one that fills Gropius Bau with the aroma of fish sauce and lemongrass, as ping-pong balls are volleyed in the atrium. It’s something this historic building has never seen before.

›Rirkrit Tiravanija: Das Glück ist nicht immer lustig‹ Gropius Bau, 12 SEP 2024 to 12 JAN 2025