Dominikus Müller (DM): For more than half a century, the DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Program, or BKP for short, has been a central force in Berlin’s transformation into an artistic centre on the world stage. It’s astonishing that the history of this institution has remained so unexamined and inaccessible to the public, isn’t it?

Melanie Roumiguière (MR): Absolutely, I think so too. Given the programme’s politically charged push towards internationalisation and its close ties to politics, self-critical examination of the institution’s history is even more important. It is also incumbent on any institution to look back on their own development in an honest, clear-eyed way so that a clearer path can be mapped out for the future. Actually, working through this historical aspect was really at the forefront of my mind when I applied to lead the visual arts division. Close to the start of my tenure five years ago, I made a point of heading to the archive—although whether one could really call it an ›archive‹ is open to debate. The fact is that, while there was quite a bit of material, much of it remained unsorted and unorganised. Rows of cardboard boxes, shrink-wrapped and stacked on pallets, lay dormant for three decades in an outdoor storage enclave. These documents were just entirely detached from reality—languishing in obscurity both inside and outside the institution. So, the first task involved simply was looking at and organizing all these materials. Then, in a second phase, it was about digitising them and making them available online. Here I should also stress that this ambitious project would not have been possible without external funding provided by digiS.

DM: So now the results of these years of research are being presented in three exhibitions at daadgalerie, Neuer Berliner Kunstverein (n.b.k.), and Galerie im Körnerpark, all concurrent with Berlin Art Week. There will also be events at Akademie der Künste. What can people expect to see?

MR: We organised the exhibitions together with Nóra Lukács, who it so happens is researching for her doctorate on the significance of West Berlin for artists from socialist countries, parallel to my research here at the institution. This was a real stroke of luck, as it added an important outside perspective. All the institutions involved in this project have a long-standing history with the DAAD. And all three exhibitions focus on mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion. Our aim is to highlight voices and perspectives that may not have been prominent in the institution’s rhetoric to date but are certainly discoverable in the archives.

DM: What does that entail specifically?

Nóra Lukács (NL): A major focus of the n.b.k. will be the relationship to the city and the role of public space, as well as the importance the programme ascribed to Eastern European nations and connections to East Berlin. Specifically, we’ll look at EP Galerie, helmed by Jürgen Schweinebraden in Prenzlauer Berg in the 1970s, where several BKP fellows exhibited. It’s striking that these connections have so far been almost completely absent from the institution’s self-description. Here, we’ll be looking closely at the introspection of the artists themselves—a big topic, especially for female artist fellows like Maria Lassnig, Dorothy Iannone, or Shigeko Kubota. We’ll also be showing work from Maija Tabaka, the first artist to come from the former Soviet Union to West Berlin. Her work will be juxtaposed with that of female figures in the important Critical Realism movement of the period, including Bettina von Arnim and Maina-Miriam Munsky.

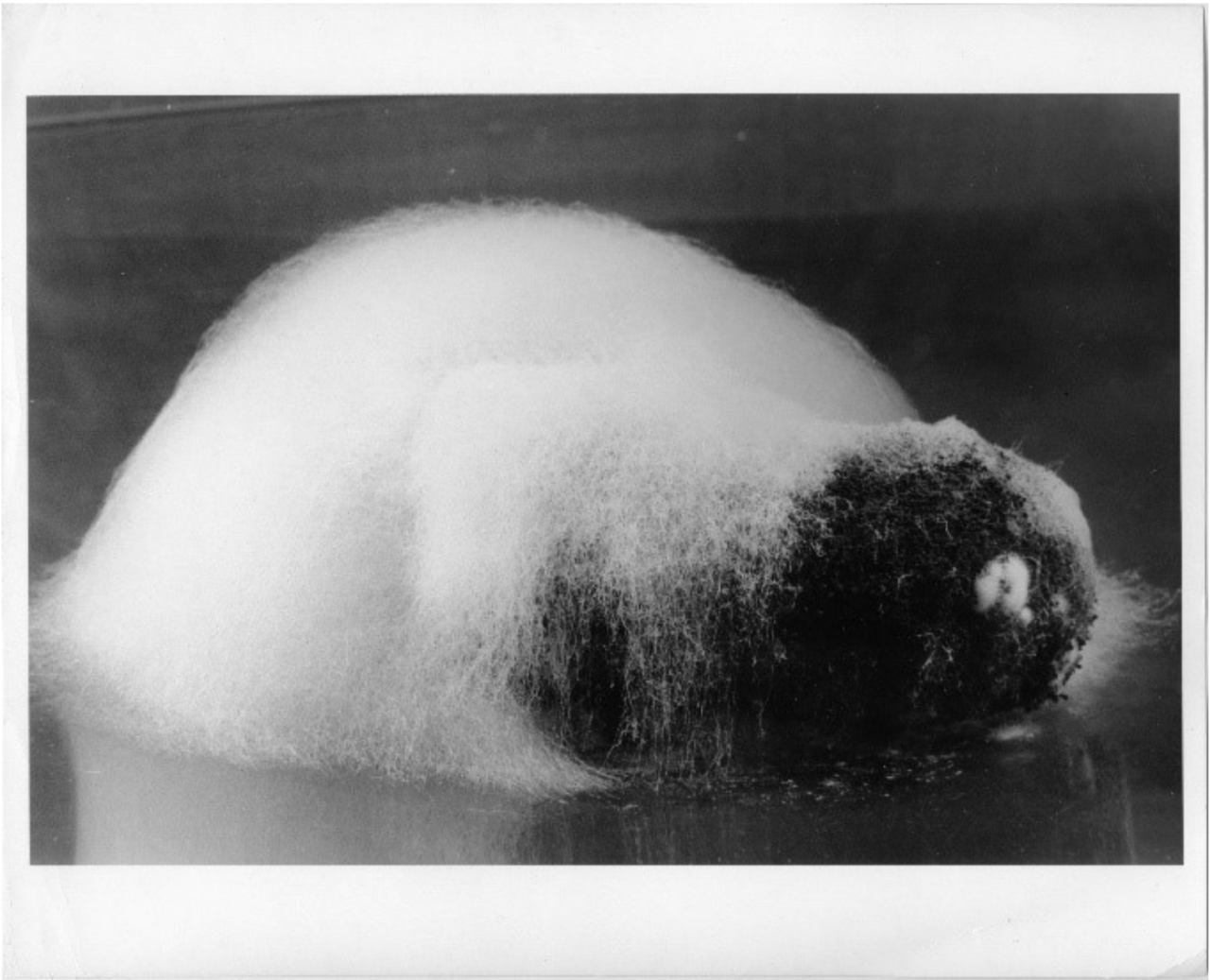

DM: Then at Galerie im Körnerpark, there’s a solo exhibition featuring Agnes Denes. What’s the reason for focusing on her in this context?

NL: Even in her early work from the 1970s, which we’re showing here, Denes demonstrated a strong interest in the intersection of art and science, but also cultural and biological evolution—in essence, the continued existence of our world. She was awarded a BKP fellowship in 1978, although she never took up the fellowship, despite constant communication to the contrary. In fact, she actively tried to do the fellowship until the late 1990s, but nothing ever came of it. We also want to openly address this glaring omission where, despite official statements, her fellowship never came about.

DM: Why do you think that is?

MR: For one thing there were practical reasons, including the specific timing of her residency. But it was also due to the fact that Denes’s vision for her residency didn’t fit in with how the programme was structured, or perhaps what it was willing to accommodate. Her complex way of working would have required interaction with the scientific community and the transport of her technical equipment from the USA—and these conditions couldn’t or wouldn’t be met. Moreover, a close look at other material in the archive provides insight into the broader pattern of how female artists in general faced significant obstacles in their attempts to gain access to the programme. The conditions they encountered were often markedly different. For example, when proposing artistic concepts that deviated from their established practices, or when seeking opportunities to present their work, the circumstances varied considerably. Yvonne Rainer, for example, had originally intended to produce films in the city rather than just work as a choreographer. But she found herself embroiled in lengthy discussions.

DM: And what will be the focus at daadgalerie?

NL: We’ll be looking at the origins of the project and its cultural and political dimensions, as well as the situation of the fellows who came here at that time. In addition, we’ve invited contemporary artists to articulate their perspectives on the BKP and the archival material. Contemporary&, for example, will be installing their ›Center of Unfinished Business‹ while Sonya Schönberger, Isaac Chong Wai, Alicja Rogalska, and others have contributed new works to the exhibition project. It’s also important to look at areas of tension between the idea of internationalising art in West Berlin and the status of the local art scene.

»There was a lot of emphasis throughout the research on identifying who had the authority to decide who would come here and who wouldn’t. And from which geographical or political contexts the artists came.«—Nóra Lukács

DM: So let’s circle back to the history then and start from the beginning. When was the BKP founded?

MR: The programme actually wasn’t set up by the DAAD in 1963, it was initiated by the Ford Foundation. The official name was probably ›Artist Residency Program Berlin‹, although the documents aren’t entirely clear on that point. I view it as something of a propaganda project, even if it wasn’t explicitly stated. These days we know more about the Ford Foundation’s ties to entities like the CIA. The aim of the residency programme, as it says in the documents, was to »prevent the cultural isolation of West Berlin«. As a result, the artistic agenda was influenced by the political alliances of the time and the role of the Allies in the city. In my historical research, I was particularly interested in how the inter-institutional landscape of the city was shaped.

DM: In other words, the programme’s collaboration with local art institutions?

MR: Exactly. After the division of Berlin, most of the important museums were located in the eastern part of the city. So new institutions had to be built in West Berlin. Furthermore, after the war, many important works of art were either lost or destroyed. There were significant gaps in the collections. So, programmes like the ›Artist Residency Program Berlin‹ and later the DAAD’s BKP played an important role in the reconstruction process.

DM: In what sense?

MR: Well, there wasn’t an official cultural policy for West Berlin at the time. More like it wasn’t even allowed. It only became possible in the 1970s, after the Four Power Agreement on Berlin. Before that, the city lacked the necessary political standing. As a result, funding for the programme came directly from the federal government. It functioned as a form of project and artist support, but implicitly it also supported numerous institutions throughout the city. Interestingly, the almost exclusively male and predominantly white directors of these local institutions sooner or later all served on the programme’s jury, deciding who could come here. With the artists they invited themselves, they continued to shape their institution’s programme and, in a roundabout way, had the costs covered by the DAAD. From this point of view, the BKP played a rather important role at the time, enabling international exhibitions to take place under the prevailing circumstances.

DM: So, the role of these juries isn’t just central to the history and direction of the programme, but also to its impact on specific local cultural policies?

NL: Absolutely. There was a lot of emphasis throughout the research on identifying who had the authority to decide who would come here and who wouldn’t. And from which geographical or political contexts the artists came. It was crucial to understand the criteria used and where these criteria were rooted. Was the process openly discussed? Was it transparent? I have to say unequivocally: No, it wasn’t, as I personally experienced during my time as a researcher who was initially denied access to the archive.

»Some of the artists who came here forged connections to the local scene, but these connections were never given any kind of robust support. Many felt isolated, trapped in a kind of bubble.«—Melanie Roumiguière

MR: That has fortunately changed in the meantime. But until a few years ago, before Silvia Fehrmann took over as the new director of the programme, the make-up of the jury was not publicly known. It’s important to look at this history and discuss ways of working that are problematic from today’s perspective.

DM: Can you give a specific example from your research?

MR: Take Werner Haftmann, for instance. He was director of the Neue Nationalgalerie from 1967 to 1974, and thanks to research by Julia Voss and others at the Deutsches Historisches Museum, we now know that he was an active member of the SS during the Nazi era. Haftmann was a member of the jury for ten years. That’s ten years in which he played a role in deciding who was invited to come here and whose work he could subsequently exhibit. There has been absolutely zero communication about this—nor has there been any exploration of the direct impact that these forms of seemingly ›generous support‹ had on the art exhibited, the artists supported and, of course, the public.

DM: So, one can imagine that there was a certain notion of art being promoted that was rooted in Western, white, and abstract ideals, with a connotation of liberalism?

MR: Exactly. Also, because of these structures, local artistic scenes were often excluded from funding opportunities. The result is a constant struggle for resources that continues to this day. Some of the artists who came here forged connections to the local scene, but these connections were never given any kind of robust support. Many felt isolated, trapped in a kind of bubble. The official discourse rarely addressed these connections. One exception was the ›Szene Berlin Mai ‘72‹ project initiated by René Block. The project highlighted the interplay between BKP fellows and the local art scene, which included figures such as KP Brehmer, Wolf Vostell, and Wolf Kahlen. This project critically examined the role of the BKP. And here too, only men were involved, without exception. In any case, the discourse of the BKP was dominated by a recurring set of names from which the programme derived its prestige—figures like John Cage, Nam June Paik, Michelangelo Pistoletto, and Marcel Broodthaers. These artists, now immensely famous, were sometimes in the early stages of their careers. In contrast, we want to look at our own history and the ever-growing list of nearly 1,200 artists from a different perspective. It’s important to highlight the position of women in this context. They were few at the beginning, but they were there.

»The Eastern European authorities thought it completely unacceptable that cultural policy in West Berlin should be facilitated with funds from the West German capital, Bonn.«—Nóra Lukács

DM: How significant was West Berlin’s status as a ›frontline city‹ during the Cold War?

NL: It certainly played a major role. When you set up a programme for the internationalisation of West Berlin during the Cold War, you can’t ignore the socialist countries. But even there, you had certain gatekeepers who decided who could participate and who couldn’t. In most cases, these were non-conformist artists who disagreed with the cultural and political values of their home countries. But there were exceptions, such as the Latvian painter Maija Tabaka. A parallel invitation process was even developed to facilitate exit permits for artists from these countries. The Eastern European authorities thought it completely unacceptable that cultural policy in West Berlin should be facilitated with funds from the West German capital, Bonn. All this hasn’t been thoroughly researched until now, and we hope that our exhibition project will bring this history into the public sphere for discussion. It’s also interesting to note that many Eastern European artists worked in public space. While this was often an important part of their artistic practice, one could also question whether this was influenced by their lower profile and representation in local art institutions due to the propagated Western individualised approach to art. Similarly, the fellows’ recurrent interest in the circumstances of guest workers in Berlin raises the question of whether this focus on a group that the German public tends to neglect is linked to a certain sense of isolation within the city.

»For an institution like ours, which has a strong connection to politics, it’s crucial to reflect on our selection criteria and narratives, and to draw a clear line between ourselves and politics.«—Melanie Roumiguière

DM: Going back to the start of our conversation: Melanie, you mentioned earlier that coming to terms with history is important when it comes to shaping the future direction of an institution. What are your expectations or hopes for the ongoing archive project at DAAD?

MR: I would like to think that we can learn valuable lessons from the past that can guide our decisions in the future. By examining history from today’s perspective, particularly with the input of voices and knowledge from outside the institution, we can shape the way the programme operates. It’s an ongoing process. For an institution like ours, which has a strong connection to politics, it’s crucial to reflect on our selection criteria and narratives, and to draw a clear line between ourselves and politics.

DM: And that’s where a look into the institution’s own history becomes indispensable.

MR: Exactly. Until now, the history of the BKP has been a closed book. But discussing what happened is crucial. It’s only then that we can we reassess our institutional practices and keep them conscious as elements that define an institution beyond its programmatic focus. This is where the capacity for self-reflection really comes into play. Now, like all institutions, we are compelled to respond—and thankfully so. We must not only find ways to shed light on those who have been invisible, but also create spaces that are truly open to engagement. This means, above all, stepping back as an institution and providing the relevant material for the fellows who come to us, as well as for others who want to engage with our institution’s history. There are artists who incorporate these histories into their practice. The art exists. We don’t have to come up with it ourselves. On the contrary, we must admit that we know and can know only a fraction of it. So, the most important task is to facilitate situations that allow the relevant individuals and networks, the voices and knowledge, to find their place. I’d like this project to serve as a starting point for that.